I was browsing the pages of Net Galley and ran across this gem of a memoir. Often when someone that isn’t famous gets an autobiography published by a major publisher, it’s a hint to the reader that the story will be riveting. Such is the case here; my many thanks go to Net Galley and Atria for the DRC, which I read free in exchange for this honest review. You can order it now’ it comes out Tuesday, May 9.

I was browsing the pages of Net Galley and ran across this gem of a memoir. Often when someone that isn’t famous gets an autobiography published by a major publisher, it’s a hint to the reader that the story will be riveting. Such is the case here; my many thanks go to Net Galley and Atria for the DRC, which I read free in exchange for this honest review. You can order it now’ it comes out Tuesday, May 9.

It probably says a great deal, all by itself, that I had never heard of Booker Wright before this. I have a history degree and chose, at every possible opportunity, to take classes, both undergraduate and graduate level, that examined the Civil Rights Movement, right up until my retirement a few years ago. As a history teacher, I made a point of teaching about it even when it wasn’t part of my assigned curriculum, and I prided myself on reaching beyond what has become the standard list that most school children learned. I looked in nooks and crannies and did my best to pull down myths that cover up the heat and light of that critical time in American history, and I told my students that racism is an ongoing struggle, not something we can tidy away as a fait accompli.

But I had never heard of Booker.

Booker Wright, for those that (also) didn’t know, was the courageous Black Mississippian that stepped forward in 1965 and told his story on camera for documentary makers. He did it knowing that it was dangerous to do so, and knowing that it would probably cost him a very good job he’d had for 25 years. It was shown in a documentary that Johnson discusses, but if you want to see the clip of his remarks, here’s what he said. You may need to see it a couple of times, because he speaks rapidly and with an accent. Here is Booker, beginning with his well-known routine waiting tables at a swank local restaurant, and then saying more:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GM-zG…

So it was Booker and his new-to-me story that made me want to read the DRC. Johnson opens with information from that time, but as she begins sharing her own story, discussing not only Booker but her family’s story and in particular, her own alienation from her mother, who is Booker’s daughter, I waited for the oh-no feeling. Perhaps you’ve felt it too, when reading a biography; it’s the sensation we sometimes feel when it appears that a writer is using a famous subject in order to talk about themselves, instead. I’ve had that feeling several times since I’ve been reading and reviewing, and I have news: it never happened here. Johnson’s own story is an eloquent one, and it makes Booker’s story more relevant today as we see how this violent time and place has bled through to color the lives of its descendants.

The family’s history is one of silences, and each of those estrangements and sometimes even physical disappearance is rooted in America’s racist heritage. Johnson chronicles her own privileged upbringing, the daughter of a professional football player. She went to well-funded schools where she was usually the only African-American student in class. She responded to her mother’s angry mistrust of Caucasians by pretending to herself that race was not even worth noticing.

But as children, she and her sister had played a game in which they were both white girls. They practiced tossing their tresses over their shoulders. Imagine it.

Johnson is a strong writer, and her story is mesmerizing. I had initially expected an academic treatment, something fairly dry, when I saw the title. I chose this to be the book I was going to read at bedtime because it would not excite me, expecting it to be linear and to primarily deal with aspects of the Civil Rights movement and the Jim Crow South that, while terrible, would be things that I had heard many times before. I was soon disabused of this notion. But there came a point when this story was not only moving and fascinating, but also one I didn’t want to put down. I suspect it will do the same for you.

YouTube has a number of clips regarding this topic and the documentary Johnson helped create, but here is an NPR spot on cop violence, and it contains an interview of Johnson herself from when the project was released. It’s about 20 minutes long, and I found it useful once I had read the book; reading it before you do so would likely work just as well:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_xxeh…

Johnson tells Booker’s story and her own in a way that looks like effortless synthesis, and the pace never slackens. For anyone with a post-high-school literacy level, an interest in civil rights in the USA, and a beating heart, this is a must-read. Do it.

Grant and Sherman are my favorite generals of all time, and Flood is a highly respected author. This book was on my must-read list, and so I searched it out on an annual pilgrimage to Powell’s City of Books, and I came home happy. It turned out to be even better than I anticipated.

Grant and Sherman are my favorite generals of all time, and Flood is a highly respected author. This book was on my must-read list, and so I searched it out on an annual pilgrimage to Powell’s City of Books, and I came home happy. It turned out to be even better than I anticipated.

Are the classic “Little House” books memoir or historical fiction, and were they written by Laura or by her daughter? If you’re confused, you’re not alone. In this epic, absorbing biography of her great-grandmother, Fraser tells us. Between her congenial narrative and careful, detailed documentation, this author has created a masterpiece. Lucky me, I read it free and early thanks to Net Galley and Henry Holt Publishers. This book is now for sale.

Are the classic “Little House” books memoir or historical fiction, and were they written by Laura or by her daughter? If you’re confused, you’re not alone. In this epic, absorbing biography of her great-grandmother, Fraser tells us. Between her congenial narrative and careful, detailed documentation, this author has created a masterpiece. Lucky me, I read it free and early thanks to Net Galley and Henry Holt Publishers. This book is now for sale.

Fans of Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart will want to read this biography, written by the author that recently wrote a biography of John Wayne. I was invited to read and review by Net Galley and Simon and Schuster, and so I read it free in exchange for this honest review. It’s for sale now.

Fans of Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart will want to read this biography, written by the author that recently wrote a biography of John Wayne. I was invited to read and review by Net Galley and Simon and Schuster, and so I read it free in exchange for this honest review. It’s for sale now. I posted this review almost two years ago, and at the time most of us considered that Petty had a lot of gas left in his tank. Of all the musical memoirs and biographies I have read–and there are many–this is the one I loved best. The loss of this plucky badass rocker hit me harder than the death of any public figure since Robin Williams died, so reposting this here is my way of saying goodbye to him. Hope he’s learning to fly.

I posted this review almost two years ago, and at the time most of us considered that Petty had a lot of gas left in his tank. Of all the musical memoirs and biographies I have read–and there are many–this is the one I loved best. The loss of this plucky badass rocker hit me harder than the death of any public figure since Robin Williams died, so reposting this here is my way of saying goodbye to him. Hope he’s learning to fly. Hannibal was the first general to defeat the forces of Rome, and Hunt is the man qualified to tell us about it. I read my copy free and early thanks to Net Galley and Simon and Schuster. This book becomes available to the public July 11, 2017.

Hannibal was the first general to defeat the forces of Rome, and Hunt is the man qualified to tell us about it. I read my copy free and early thanks to Net Galley and Simon and Schuster. This book becomes available to the public July 11, 2017.

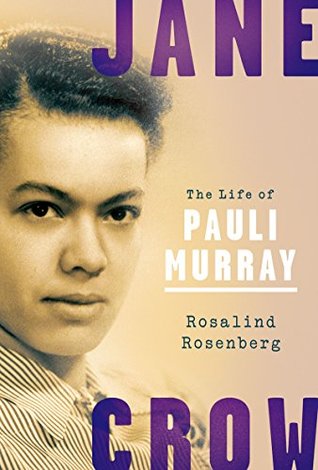

Pauli Murray is the person that coined the term “Jane Crow”, and was the first to legally address the twin oppressions of color and gender. I had seen her name mentioned in many places, but this is the first time I’ve read her story. Thank you to Net Galley and Oxford University Press for the opportunity to read it free in exchange for this honest review. This biography is for sale now.

Pauli Murray is the person that coined the term “Jane Crow”, and was the first to legally address the twin oppressions of color and gender. I had seen her name mentioned in many places, but this is the first time I’ve read her story. Thank you to Net Galley and Oxford University Press for the opportunity to read it free in exchange for this honest review. This biography is for sale now.

I was browsing the pages of Net Galley and ran across this gem of a memoir. Often when someone that isn’t famous gets an autobiography published by a major publisher, it’s a hint to the reader that the story will be riveting. Such is the case here; my many thanks go to Net Galley and Atria for the DRC, which I read free in exchange for this honest review. You can order it now’ it comes out Tuesday, May 9.

I was browsing the pages of Net Galley and ran across this gem of a memoir. Often when someone that isn’t famous gets an autobiography published by a major publisher, it’s a hint to the reader that the story will be riveting. Such is the case here; my many thanks go to Net Galley and Atria for the DRC, which I read free in exchange for this honest review. You can order it now’ it comes out Tuesday, May 9.