Charlie Chaplin rose to fame over 100 years ago, but his fame hasn’t faded over the years. One of the most visionary movie makers in modern history, he rose from desperate poverty and homelessness during his childhood to become one of the wealthiest and most respected men in his chosen profession. And yet, for some odd reason, the U.S. government relentlessly pursued him as if he were an enemy agent, eventually forcing him to retire abroad. It’s a bizarre episode in U.S. history, and a fascinating one.

When I saw that Scott Eyman, an author whose biographies of actors I have previously enjoyed—John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, Henry Fonda—had written about this case, I had to read it. My thanks go to NetGalley and Simon and Schuster for the invitation to read and review. This book is for sale now.

Charlie was born in 1889 in London. His mother Hannah was an actress, a loving mother whose health was dreadful. In addition to more conventional illnesses, she was sent repeatedly, and for longer stretches each time, to mental hospitals; it has been speculated that she suffered from syphilis, which eventually had devastating effects on her brain. Charlie’s father was a businessman who left the family and refused to pay a single shilling of child support because one of Charlie’s brothers was conceived with another man. And as an aside, if there is an afterlife, I sincerely hope that Charles Chaplin, Senior is roasting eternally in the flames of hell.

For a while, Hannah’s relatives cared for Charlie and his older brother, Syd, but eventually the boys found themselves in a workhouse, beaten, abused, sickened, and barely fed. It was his brother Syd who first discovered that acting could keep him out of the workhouse and put food on the table, and once he was so employed, Syd took his pale, sickly little brother to the theater and persuaded his boss to use Charlie, too. Thus was a star born.

His tremendous suffering during his childhood gave Charlie a lifelong sympathy with the working class, the impoverished, and the down and out. Early in his career, a director gave Charlie a costume and told him to come up with a character, and this was when he invented The Little Tramp.

I’ve known for most of my life about Charlie’s expulsion from the U.S., but I’ve never been sure whether he was a Communist. I’ve known people brought up in Communist households in America, and for many years, they existed strictly underground, so I wondered, did Chaplin deny his affiliation because he wasn’t a Communist, or because he was? Eyman’s meticulous research demonstrates once and for all that Charlie was not political. He told the truth about himself: “I am not a Communist. I am a peace monger.”

Nevertheless, once he gained prominence in the American movie industry, he had a target on his back. It’s difficult to understand why politicians and bureaucrats in California and in Washington, D.C. hated him so fiercely.

“A month after the revocation of [Chaplin’s] reentry permit, the FBI issued a massive internal report documenting more than thirty years of investigations focused on Chaplin, a copy of which was dispatched to the attorney general. The report revealed that, besides the FBI, Army and Navy Intelligence, the Internal Revenue Service, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Department of State, and the U.S. Postal Service had all been surveilling Chaplin at one time or another. In short, the entire security apparatus of the United States had descended upon a motion picture comedian.”

Eyman has done a wonderful job here. Because I had fallen behind, I checked out the audio version of this book from Seattle Bibliocommons, and I alternately listened to it and read the digital review copy. Of course, anyone reading this book for the purpose of academic research should get a physical copy, but those reading for pleasure may enjoy the audio, which is well done; this is a through, and a lengthy biography, and the audio makes it go by more quickly.

I confess I haven’t read any other Chaplin biographies, so I cannot say for certain whether this one is the best, but it’s hard to imagine a better one. For those sufficiently interested to take on a full length biography, this book is highly recommended.

Where were you when you heard that Robin Williams had died?

Where were you when you heard that Robin Williams had died? Fans of Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart will want to read this biography, written by the author that recently wrote a biography of John Wayne. I was invited to read and review by Net Galley and Simon and Schuster, and so I read it free in exchange for this honest review. It’s for sale now.

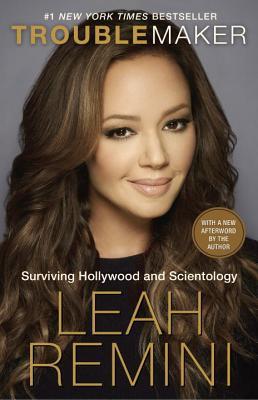

Fans of Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart will want to read this biography, written by the author that recently wrote a biography of John Wayne. I was invited to read and review by Net Galley and Simon and Schuster, and so I read it free in exchange for this honest review. It’s for sale now. Actor Leah Remini was a child when her mother discovered Scientology; the church was in many ways her parent. When she rebelled against it, she was smart and very public, and she spells the entire thing out for us right here.

Actor Leah Remini was a child when her mother discovered Scientology; the church was in many ways her parent. When she rebelled against it, she was smart and very public, and she spells the entire thing out for us right here.