Category Archives: social justice

The Song and the Silence, by Yvette Johnson*****

I was browsing the pages of Net Galley and ran across this gem of a memoir. Often when someone that isn’t famous gets an autobiography published by a major publisher, it’s a hint to the reader that the story will be riveting. Such is the case here; my many thanks go to Net Galley and Atria for the DRC, which I read free in exchange for this honest review. You can order it now’ it comes out Tuesday, May 9.

I was browsing the pages of Net Galley and ran across this gem of a memoir. Often when someone that isn’t famous gets an autobiography published by a major publisher, it’s a hint to the reader that the story will be riveting. Such is the case here; my many thanks go to Net Galley and Atria for the DRC, which I read free in exchange for this honest review. You can order it now’ it comes out Tuesday, May 9.

It probably says a great deal, all by itself, that I had never heard of Booker Wright before this. I have a history degree and chose, at every possible opportunity, to take classes, both undergraduate and graduate level, that examined the Civil Rights Movement, right up until my retirement a few years ago. As a history teacher, I made a point of teaching about it even when it wasn’t part of my assigned curriculum, and I prided myself on reaching beyond what has become the standard list that most school children learned. I looked in nooks and crannies and did my best to pull down myths that cover up the heat and light of that critical time in American history, and I told my students that racism is an ongoing struggle, not something we can tidy away as a fait accompli.

But I had never heard of Booker.

Booker Wright, for those that (also) didn’t know, was the courageous Black Mississippian that stepped forward in 1965 and told his story on camera for documentary makers. He did it knowing that it was dangerous to do so, and knowing that it would probably cost him a very good job he’d had for 25 years. It was shown in a documentary that Johnson discusses, but if you want to see the clip of his remarks, here’s what he said. You may need to see it a couple of times, because he speaks rapidly and with an accent. Here is Booker, beginning with his well-known routine waiting tables at a swank local restaurant, and then saying more:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GM-zG…

So it was Booker and his new-to-me story that made me want to read the DRC. Johnson opens with information from that time, but as she begins sharing her own story, discussing not only Booker but her family’s story and in particular, her own alienation from her mother, who is Booker’s daughter, I waited for the oh-no feeling. Perhaps you’ve felt it too, when reading a biography; it’s the sensation we sometimes feel when it appears that a writer is using a famous subject in order to talk about themselves, instead. I’ve had that feeling several times since I’ve been reading and reviewing, and I have news: it never happened here. Johnson’s own story is an eloquent one, and it makes Booker’s story more relevant today as we see how this violent time and place has bled through to color the lives of its descendants.

The family’s history is one of silences, and each of those estrangements and sometimes even physical disappearance is rooted in America’s racist heritage. Johnson chronicles her own privileged upbringing, the daughter of a professional football player. She went to well-funded schools where she was usually the only African-American student in class. She responded to her mother’s angry mistrust of Caucasians by pretending to herself that race was not even worth noticing.

But as children, she and her sister had played a game in which they were both white girls. They practiced tossing their tresses over their shoulders. Imagine it.

Johnson is a strong writer, and her story is mesmerizing. I had initially expected an academic treatment, something fairly dry, when I saw the title. I chose this to be the book I was going to read at bedtime because it would not excite me, expecting it to be linear and to primarily deal with aspects of the Civil Rights movement and the Jim Crow South that, while terrible, would be things that I had heard many times before. I was soon disabused of this notion. But there came a point when this story was not only moving and fascinating, but also one I didn’t want to put down. I suspect it will do the same for you.

YouTube has a number of clips regarding this topic and the documentary Johnson helped create, but here is an NPR spot on cop violence, and it contains an interview of Johnson herself from when the project was released. It’s about 20 minutes long, and I found it useful once I had read the book; reading it before you do so would likely work just as well:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_xxeh…

Johnson tells Booker’s story and her own in a way that looks like effortless synthesis, and the pace never slackens. For anyone with a post-high-school literacy level, an interest in civil rights in the USA, and a beating heart, this is a must-read. Do it.

The Standard Grand, by Jay Baron Nicorvo*****

“A loaded gun wants to go off.”

“A loaded gun wants to go off.”

Critics have compared Nicorvo’s brilliant debut novel to the work of Heller, and indeed, it seems destined to become the go-to story of those that have served in the unwinnable morass created by the US government against the people of the Middle East: “a drawdown war forever flaring up”. It’s created a tremendous amount of buzz already. I was lucky enough to read it free and in advance for the purpose of a review, thanks to Net Galley and St. Martin’s Press, but today it’s available to the public. You should buy it and read it, maybe more than once.

The story starts with a list of the characters involved, but the way it’s presented provides a tantalizing taste of the author’s voice. The page heading tells us these are “The Concerns”, and the subheadings divide them into practical categories, such as The Smith Family, the Employees of IRJ, Inc., and The Veterans of The Standard Grande (misspelling is mentioned later in the story). Then we proceed to list The Beasts, and The Dead, and The Rest, and right then I know this is going to be good.

Antebellum Smith is our protagonist, and she’s AWOL, half out of her mind due to PTSD, anxiety, and grief. She’s sleeping in a tree in New York City’s Central Park when Wright finds her there and invites her to join his encampment at The Standard Grand. Here the walking wounded function as best they can in what was once an upscale resort. One of the most immediately noticeable aspects of the story is the way extreme luxury and miserable, wretched poverty slam up against one another. Although the veterans are grateful for The Standard Grand, the fact is that without central heat, with caved in ceilings, rot, and dangerous disrepair, the place resembles a Third World nation much more than it resembles the wealthiest nation on the planet.

On the other hand, it’s also perched, unbeknownst to most of its denizens, on top of a valuable vein of fossil fuel, and the IRJ, Incorporated is sending Evangelina Cavek, their landsman, out in a well-appointed private jet to try to close the deal with Wright. She is ordered off the property, and from there things go straight to hell.

Secondary and side characters are introduced at warp speed, and at first I highlight and number them in my reader, afraid I’ll lose track of who’s who. Although I do refer several times to that wonderful list, which is happily located right at the beginning where there’s no need for a bookmark, I am also amazed at how well each character is made known to me. Nicorvo is talented at rendering characters in tight, snapshot-like sketches that trace for us, with a few phrases and deeds, an immediate picture that is resonant and lasting. Well drawn settings and quirky characters remind me at first of author James Lee Burke; on the other hand, the frequently surreal events, sometimes fall-down-funny, sometimes dark and pulse-pounding, make me think of Michael Chabon and Kurt Vonnegut. But nothing here is derivative. The descriptions of the main setting, The Standard Grand, are meted out with discipline, and it pays off.

As for Smith, she still has nightmares, still wakes up to “the voices of all the boys and girls of the wars—Afghan, Iraqi, American—like a choir lost in a dust storm.”

There’s so much more here, and you’re going to have to go get it for yourself. It’s gritty, profane, and requires a reasonably strong vocabulary level; I’m tempted to say it isn’t for the squeamish, yet I think the squeamish may need it most.

Strongly recommended for those that love excellent fiction.

Beartown, by Fredrik Backman****

“You can fuck any girl you like here tonight; they’re all hockey-whores when we win.”

“You can fuck any girl you like here tonight; they’re all hockey-whores when we win.”

Fredrik Backman is a sly writer, and he has a way of spiraling around his central point so that readers are mighty close by the time they recognize where they are. He writes with philosophical grace tinged with wit, and his novels are popular because of it. And so it cheers me to see him examine what might happen to a small depressed town whose hopes are all hinged on youth sports. Thanks go to Net Galley and Atria Books for the DRC, which I read free of charge in exchange for this honest review. Beartown is available to the public today.

In Beartown, everyone dreams of hockey, and those that don’t are stuck on the outside looking in. A man’s glory days are done before he’s 40; a woman has no glory days at all, since women cannot play on the men’s team and there is no women’s team. Everything comes second to hockey: education, social skills, and even the law are bent, sometimes to the breaking point, in order to accommodate star athletes. Hockey is the town’s only remaining business, and it seems to provide the only possible hope for young men that have grown up in the forest and don’t want to leave it to seek work.

Backman has a genius for drawing the reader in. Some of the scenes in this story actually make me laugh out loud. His respect for women is a breath of fresh air as well. In literary terms, though, the greatest success of this piece is the way a large number of characters are developed so that readers genuinely feel that we know not just a protagonist, but a whole town. We know who is related, what private baggage exists between individuals and families, which marriage is happy and which is not, and it’s delivered to us in a way that never feels gossipy or prurient. Rather, Backman makes us feel as if we are part of the town, and so everything is important to us as well.

Fans of Backman’s will be pleased once again here. My sole quibble is that I see a character at the end behave in a way that is so inconsistent with what we know of him so far that I can hear the violins play. It’s heartwarming, but if the same thing had been achieved more subtly, it would be credible as well.

Nevertheless, you won’t want to miss this book. Regardless of the ugly things that are said and done at various points, the author comes back, as he always has before, to the innate goodness of the human spirit, and it’s messages like this one that we need so badly today. Recommended to those that enjoy good fiction.

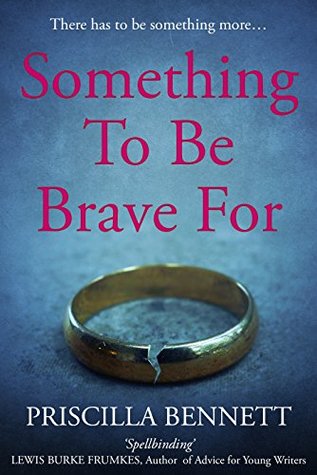

Something To Be Brave For, by Priscilla Bennett***

Bennett’s provocative new novel tackles domestic abuse. I was invited to read this one free and in advance by a representative from Endeavor Press in exchange for an honest review.

Katie Giraud is the daughter of a successful surgeon. Her father is disappointed when she chooses not to go into medicine, but he is overjoyed when she falls in love with his protégé, Claude Giraud. Claude is the son he never had. Katie is an art lover, and now she can enjoy her passion while being well provided for. Her husband is a handsome, charming Frenchman who woos her with roses and jewelry. It’s like something out of a fairy tale.

Katie Giraud is the daughter of a successful surgeon. Her father is disappointed when she chooses not to go into medicine, but he is overjoyed when she falls in love with his protégé, Claude Giraud. Claude is the son he never had. Katie is an art lover, and now she can enjoy her passion while being well provided for. Her husband is a handsome, charming Frenchman who woos her with roses and jewelry. It’s like something out of a fairy tale.

The trouble commences when the wedding is done and real life begins. You see, Claude has a wicked temper. He has enormous control issues, and he’s unpredictable. You just don’t know when he’s going to lash out. Next thing she knows, Katie is bleeding and cowering beneath the grand piano. But after daughter Rose is born, things are better, but they’re worse; Katie is more willing to try to escape this abusive relationship because she knows that it traumatizes her little girl to see Claude hurt her, but having a daughter also makes flight more complicated.

It isn’t as easy as it sounds.

Feminists everywhere can rejoice that the problem is so well demonstrated. Even in a home where there is such affluence, leaving isn’t as easy as it sounds. Her husband’s reputation is excellent, and he’s a smooth liar. Her parents love him, and he’s friends with the chief of police. Every effort she makes is thwarted. I appreciate this as I read it, because in cases of domestic abuse, societal conversation tends to question the victim: what is wrong with her, to make her stay in a situation like that? Why not develop a spine, get up, walk out? And yet statistics tell us that a woman is much more likely to be killed by a violent spouse, or former spouse, after she has left him, than to be killed by him while still in the marriage.

Leaving is dangerous.

That said, it seems strange that I never feel bonded to Katie. I know she is an art lover, a battered wife, and a devoted mother, and I know some of her physical attributes, but beyond these things her character remains blurry and underdeveloped. Better character development would move the entire story forward and add greater impact to the overall message.

The ending feels simplistic and somewhat formulaic. But those that care about domestic violence and champion women’s issues may want to read it anyway because it adds to the discussion, one that so often is stifled as its victims remain isolated in the shadows.

This book was published April 3, 2017 and is available for sale now.

It Happens All the Time, by Amy Hatvany***

I was invited to read and review this title in advance by Net Galley and Atria Books; it is written by a rape survivor, who tells us bravely of her own experience in the introduction. I wanted to love this book and to scream it across the internet and from the top of the Space Needle, that everyone should get it and read it, but instead, I came away feeling ambivalent. The rape passage is resonant and horrifying, and it’s written in a courageous way, and I’ll go into that in a minute. The rest of the book, however, is flat, and so in some ways this proves to be an opportunity squandered. There are spoilers, so don’t proceed if you don’t want to know how the book ends. It is available for purchase today.

I was invited to read and review this title in advance by Net Galley and Atria Books; it is written by a rape survivor, who tells us bravely of her own experience in the introduction. I wanted to love this book and to scream it across the internet and from the top of the Space Needle, that everyone should get it and read it, but instead, I came away feeling ambivalent. The rape passage is resonant and horrifying, and it’s written in a courageous way, and I’ll go into that in a minute. The rest of the book, however, is flat, and so in some ways this proves to be an opportunity squandered. There are spoilers, so don’t proceed if you don’t want to know how the book ends. It is available for purchase today.

The premise is that Amber and Tyler are best friends. They dated when they were teenagers, but a lot of time has gone by, and they have agreed to be buddies, talking often. Amber does not know that Tyler’s torch is still burning for her, brighter than ever; he is waiting for her to come around. Meanwhile, she has become engaged to someone else.

Amber is also a recovering bulimic, and now she is a specialist in nutrition and fitness. The level of detail regarding Amber’s meals hijacks the narrative at times; I don’t care how many ounces of lean this, that, the other she is about to eat. If we’re going to write about diet and fitness, that should be another book, and otherwise it should stay in the background.

The rape itself is where the story shines, and of course, it is the central scene to the story. Hatvany wants us to recognize who rapists are, and who they aren’t:

“They’re not greasy-haired monsters who jump out from behind the bushes and tie up their victims in their basements.”

The story is told from alternating perspectives, so we hear from both Amber and Tyler. Amber is believable to a degree; a more richly developed character would be more convincing, but the story is one that countless girls and women have lived. It’s a date that goes badly wrong; sometimes the woman is one that expects that she will want sex, but then decides she doesn’t, and her date forces the issue. Is that rape? Unless she says yes to sex, it is. Sometimes it starts with kisses—drunken or otherwise—but when the man wants to go further, she decides she wants to keep her clothes on and not follow through. If she says stop, or wait, or fails to say she wants to do this, yes, it is rape. And so this part of the narrative is important, and once I have read it, I want more than ever to like the rest of the book so that I can promote it.

Tyler is just straight up badly written. I am sorry to say it, but I rolled my eyes when I read his portion of the narrative. The ending is way over the top, and it distracts us with morally questionable deeds done by Amber that we would never commit. If it was rendered brilliantly, it could perhaps come across heroically, like Thelma and Louise, but it isn’t, and it doesn’t.

What happens here, is that Amber kidnaps Tyler post-rape at gunpoint. She forces him to drive to her family’s vacation cabin, and she makes him say that he raped her. He won’t do it, so she shoots him. She refuses to take him to a hospital until he says what she wants him to say. Once all of this happens, he has a huge epiphany, and from then on, Tyler’s wails about what a bad thing he has done, and how he knows he deserves everything that will happen to him as a result.

Sure.

But in addition, I find myself squirming. At one point when Amber holds him hostage, Tyler points out to her that kidnapping is a felony. Having Amber muddy the waters morally by kidnapping and shooting her assailant is distracting and morally tenuous at best. He has to tell the truth; she doesn’t. He owes it to her to lose his job and career, and to serve his time; she never expresses any sort of remorse and never suffers the consequences of her actions. And whereas brilliant prose stylist could turn Amber into a vigilante folk hero, this isn’t that.

I know that the author intends to tell a story that is deeply moving and that will improve the social discourse regarding what rape is, and how we as a society deal with it, both institutionally and as individuals. Instead, the distractions and tired prose prevent this story from reaching its potential.

The Devil’s Country, by Harry Hunsicker****

Harry Hunsicker is the former executive vice president of the Mystery Writers of America as well as a successful author. Reading this suspenseful and at times almost surreal tale makes it easy to understand why so many people want to read his work. I’d do it again in a heartbeat. Thanks go to Net Galley and to Thomas and Mercer for the DRC, which I received in exchange for this honest review. This book will be available to the public April 11, 2017.

Harry Hunsicker is the former executive vice president of the Mystery Writers of America as well as a successful author. Reading this suspenseful and at times almost surreal tale makes it easy to understand why so many people want to read his work. I’d do it again in a heartbeat. Thanks go to Net Galley and to Thomas and Mercer for the DRC, which I received in exchange for this honest review. This book will be available to the public April 11, 2017.

Arlo Baines, a former Texas Ranger, is on the road when it all unfolds; he’s stopped at the tiny town of Piedra Springs, traveling from one place to another by Greyhound Bus, and he doesn’t intend to stay. He finds a place to get some food, sticks his nose in a copy of Gibbon, and tries to ignore everyone around him. Friendly conversation? Thank you, but no.

Unfortunately for him, there’s a woman with kids, and she’s in big trouble. Clad in an outfit that screams sister-wife, she is terrified, tells him she is pursued, and next thing he knows, she is dead. What happened to the children? Before he knows it, Baines is hip deep in the smoldering drama of the Sky of Zion, a cult that has deep tentacles into the local business and law enforcement establishments.

The narrative shifts smoothly back and forth between the past and the present, and Baines’s motivation is revealed. He is on the move because his wife and child were murdered by corrupt cops, who he then had killed. One particularly chilling scene, the one in which Baines is told to leave town, gives me shivers. In general, however, I find that the scenes taking place in the present are more gripping and resonant than those in the past.

Interesting side characters are Boone, a retired professor with a crease on his head and flip-flops that are falling apart; the local sheriff, Quang Marsh; journalist Hannah Byrnes; and the bad guys in Tom Mix-style hats, with the crease down the front. Setting is also strong here, and I can almost taste the dust in my mouth as Baines pursues his quest in this little town with quiet determination. Every time I make a prediction, something else—and something better—happens instead. In places, it’s laugh-out-loud funny!

Readers that love a good thriller and whose world view leans toward the left will find this a deeply satisfying read. Hunsicker kicks stereotypes to the curb and delivers a story unlike anyone else’s. I would love to see this become a series.

Hungry Heart, by Jennifer Weiner*****

“I wanted to write novels for the girls like me, the ones who never got to see themselves on TV or in the movies, the ones who learned to flip through the fashion spreads of Elle and Vogue because nothing in those pictures would ever fit, the ones who learned to turn away from mirrors and hurry past their reflections and unfocus their eyes when confronted with their own image. I wanted to say to those girls, I see you. You matter. I wanted to give them stories like life rafts…I wanted to tell them what I wished someone had told me…to hang on, and believe in yourself, and fight for your own happy ending.”

“I wanted to write novels for the girls like me, the ones who never got to see themselves on TV or in the movies, the ones who learned to flip through the fashion spreads of Elle and Vogue because nothing in those pictures would ever fit, the ones who learned to turn away from mirrors and hurry past their reflections and unfocus their eyes when confronted with their own image. I wanted to say to those girls, I see you. You matter. I wanted to give them stories like life rafts…I wanted to tell them what I wished someone had told me…to hang on, and believe in yourself, and fight for your own happy ending.”

Many thanks go to Net Galley and Atria for the DRC, which I received a couple of months after the publication date. Having read this memoir makes me want to read more of this author’s work. It’s for sale now.

The fact that I’ve never read anything by this author makes me something of an outlier in terms of her target audience. I’m also slightly older than she is, not in need of a mentor. But none of that matters, because quality is quality, and feminist messages like this one are always good to read.

Weiner writes with an arresting combination of candor and wit, and she talks about the things we grew up being taught not to mention. Those of us that saw role models like Twiggy—a British model with a nearly anorexic appearance—and Mia Farrow, yet were ourselves unable to shake the persistent amount of what kindly adults called baby fat, never thought to argue that we were as worthwhile as these bony fashion icons. Weiner deals with the topic of body image and media head on. And while she’s there, she talks about facing down anti-Semitism in the classroom, and the dry hiss of another child on the playground suggesting that she has killed Jesus. She talks about also being the chunky, unfashionable member of her kibbutz to Israel in the unforgettable chapter titled “Fat Jennifer in the Promised Land”.

At times I confess I am annoyed by appear to be petit bourgeois concerns. You struggled to choose between Princeton and Smith? Oh you poor dear! But later when I read that she is called in to the administration’s offices and told to get her things and go because her tuition hasn’t been paid, I forgive her immediately.

Weiner takes on questions that many feminist writers pass by. I’ve never seen another writer address the fact that if a woman cannot successfully breast feed her baby or even just doesn’t want to, the child will most likely not starve. This and a host of other seldom spoken issues having to do with combining career and motherhood can help other mothers, whether working or taking time away from the workplace to raise a child, feel less isolated.

Every woman needs a funny female version of Mister Rogers to tell us that we are fine just the way we are. Every mother needs another woman that can tell her—sometimes in hilarious ways—that every rotten thing that ever happens to her child is not her fault.

Highly recommended for women seeking wisdom and snarky kick ass commentary, and to those that love them.

Always, by Sarah Jio****

Always, Sarah Jio’s much anticipated new release, takes on the homelessness epidemic using the powerful medium of fiction. I received my copy in advance in exchange for an honest review; thank you Net Galley and Random House Ballantine for the DRC. This title is available to the public today, and if you have enjoyed Jio’s other novels, I am confident you’ll like this one too.

Always, Sarah Jio’s much anticipated new release, takes on the homelessness epidemic using the powerful medium of fiction. I received my copy in advance in exchange for an honest review; thank you Net Galley and Random House Ballantine for the DRC. This title is available to the public today, and if you have enjoyed Jio’s other novels, I am confident you’ll like this one too.

Kailey Crane is a journalist living in Seattle during the 1990s, and she has the whole package: a great job, a wonderful city, and a wealthy, handsome fiancée. It’s the life other little girls dreamed of but didn’t get. Then one night as she and Ryan are leaving a restaurant, she literally bumps into a long lost love. Cade McAllister is the man Kailey had been going to marry until he disappeared. He practically vaporized. Stunned and humiliated, she picked herself up and rebuilt her life, and now here he is, a half-crazed homeless man living downtown on the streets.

What the heck happened?

Kailey wants to marry Ryan, but she also wants to help Cade find housing, medical care, and food. Ryan makes it easier by agreeing that she should do the right thing. Quickly she learns that it isn’t as simple as it seems. There’s a whole safety net in place for people like Cade, except that it doesn’t work. In fact, without her own ready access to Ryan’s money, she can do virtually nothing for Cade. But it’s all right, because Ryan is on the side of the angels; he sees that this cause is a just one, and he’s a generous guy. He’s in love, and he’s feeling expansive.

The problems begin when Kailey starts missing key wedding events because she’s off helping Cade, or trying to. She becomes so involved with one thing and another that before she knows it, she’s over an hour late. There are out of town relatives that are present, but where’s the bride? And before we know it, she’s telling lies, and sometimes they don’t even seem necessary. I want to reach through the pages of the book, yank Kailey into the kitchen and talk to her.

What are you doing, girl?

Fissures in her relationship with Ryan turn into fractures as he senses the level of her obsession, and he doesn’t see things as she does anymore. His material interest is involved, since a project his development corporation is about to undertake conflicts with an already established homeless shelter in Pioneer Square, a historic part of Seattle’s downtown. He questions why so many resources are required for the homeless; aren’t these mostly drug addicts and crazy people? There ought to be a simple way to dispatch the problem.

A strong story overall is somewhat tarnished by what feels like a glib ending. I recall a favorite episode of the Muppets when Miss Piggy is working a jigsaw puzzle, and she hates to be wrong, so she slams a piece into a hole where it doesn’t belong and howls, “I’ll make it fit!” The ending of this story brought the episode back to me, because Jio seems to be doing more or less the same thing.

Recommended to fans of this successful romance writer.

Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved By Beauty, by Kate Hennessy***

Dorothy Day is an interesting historical figure, the woman that founded The Catholic Worker, which was initially a combined newspaper, homeless shelter, and soup kitchen. I once subscribed to The Catholic Worker, and since it cost one penny per issue, you couldn’t beat the price. I saw this biography available and snapped it up from Net Galley; thanks go to them and Scribner, who provided me with a DRC in exchange for an honest review. This title was published in late January and is now available for purchase.

Dorothy Day is an interesting historical figure, the woman that founded The Catholic Worker, which was initially a combined newspaper, homeless shelter, and soup kitchen. I once subscribed to The Catholic Worker, and since it cost one penny per issue, you couldn’t beat the price. I saw this biography available and snapped it up from Net Galley; thanks go to them and Scribner, who provided me with a DRC in exchange for an honest review. This title was published in late January and is now available for purchase.

I always had a difficult time getting a handle on what The Catholic Worker stood for. The name suggests radicalism, and indeed, Day was red-baited during the McCarthy era. Day was a Catholic convert and a strong believer in sharing everything that she had with those that had nothing. She worked tirelessly and selflessly, and despite often living an impoverished existence somehow made it into her eighties before she died, an iconic crusader who became prominent when almost no women did so independently—though she was no feminist, and believed that wives should submit to husbands. Since her demise, speculation has arisen as to whether she might be canonized.

What was that huge crash? Was it a marble statue being knocked the hell off its pedestal? Hennessy takes on the life and deeds of her famous grandmother with both frankness and affection. In the end, I came away liking Day a good deal less than I had when I knew little about her. Her tireless effort on behalf of the poor included anything and everything her very young daughter had in this world, and at one point she remarked that she felt unable to ask others to embrace a life of poverty if her child wasn’t also a part of that. It was a different time, one with no Children’s Protective Service to come swooping down and note that the child was sleeping in an unheated building in the midst of frigid winter; that there was no running water, since the building was a squat; that the only food that day was a single bowl of thin soup and perhaps a little hard bread donated from the day-old stores of local bakeries; that even small, personal treasures and clothing given the child by other relatives and friends would either be stolen by homeless denizens or even given away by her mother, a woman with the maternal instincts of an alley cat. Day did a lot of good for a lot of people, and no one can say she did it for her own material well being, but she more or less ruined her daughter’s life, and even when grown, Tamar’s painful social anxiety and panic attacks derailed her efforts to build a normal life for herself.

Nevertheless, the immense contribution that Day made at a time when the only homeless shelters were ones with a lot of rules and sometimes religious requirements cannot be overlooked. She is said to have had a commanding presence, endless energy (and the mood swings that accompany such energy in some people), and a mesmerizing speaking voice. Day’s physician also treated the great Cesar Chavez, and reflected that their personalities were a lot alike.

I confess I was frustrated in reading this memoir, because I really just wanted the ideas behind the Catholic Worker laid out for me along with the organizational structure. Was the whole thing just whatever Day said it was at the moment, or was there democratic decision making? I never really found out, although I gained a sense that the chaotic events shown in the memoir reflected an unarticulated organizational chaos as well. This is a thing that sometimes happens with religious organizations; the material underpinnings are tossed up in the air for supernatural intervention, and the next thing they know, there’s an ugly letter from the IRS.

Only about half of this memoir was actually about Day; my sense was that the author did a lot of genealogical research and then decided to publish the result. The first twenty percent of the book is not only about Day’s various romantic entanglements; a significant portion of the text is mini-biographies of those men, and frankly, I wasn’t interested in them. I wanted to know about Day. Later I would be frustrated when long passages would be devoted to other relatives and their lives. Inclusion of daughter Tamar was essential, because Dorothy and Tamar were very close all their lives and shared a lot, and so in some ways to write about one was to tell about the other. But I didn’t need to know about Day’s in-laws, her many and several grandchildren, and so on. I just wanted to cut to the chase, but given the nature of the topic, also didn’t want to read Day’s own writing, which has a religious bias that doesn’t interest me.

Those with a keen interest in Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker may want to read this, because not many books are available that discuss her life and work. On the other hand, I don’t advise paying full cover price. Get it free or at a deep discount, unless you are possessed of insatiable curiosity and deep pockets.