Susan Straight is a force to be reckoned with. I knew this after I finished reading I Been in Sorrow’s Kitchen and Licked Out All the Pots after it came out in 1992, and after I sought out, bought, and read everything else she’d written that was available. When I discovered that her new novel, Mecca, was available on Net Galley, I leapt on it. My thanks go to Net Galley and to Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux for the review copy. This book is for sale now.

Mecca, an ironic title if ever there was one, is a story of race, class, and gender, and the way that they play into the “Justice” system in California. Add a generous seasoning of climate change and its horrific effects in dry, dry Southern California, and a fistful of opioid addiction, and you have a heady mix indeed. But these are all well worn ground at this point, and this book is exceptional, not because it examines complex current events, but because of Straight’s facility in building visceral characters we care about, and launching them into this maelstrom in a way that makes it impossible to forget.

We begin with Johnny Frias, an American citizen of Latino heritage. As a rookie and while off duty, he kills a man that is raping and about to murder a woman named Bunny. He panics and gets rid of the body without reporting what’s happened. Frias is on the highway patrol, and he takes all sorts of racist crap all day every day. But his family relies on him, and when push comes to shove, he loves his home and takes pride in keeping it safe.

Ximena works as a maid at a hotel for women that have had plastic surgery. One day she is cleaning a room and finds a baby! What to do? She can’t call the authorities; she’d be blamed, jailed, deported, or who knows what. She does the best thing she can think of, and of course, there’s blowback anyway.

And when a young Black man, a good student with loads of promise that has never been in any trouble at school, or with the law, is killed because the cops see his phone fall out of the car and decide it’s a gun…?

I find this story interesting from the beginning, but it really kicks into gear in a big way at roughly the forty percent mark. From that point forward, it owns me.

As should be evident from what I’ve said so far, this story is loaded with triggers. You know what you can read, and what you can’t. For those of us that can: Straight’s gift is in her ability to tell these stories naturally, and to develop these characters so completely that they almost feel like family. It is through caring about her characters that we are drawn into the events that take place around them, and the things that happen to them.

This is a complex novel with many moving parts and connections. I read part of this using the audio version, which I checked out from Seattle Bibliocommons. But whereas the narrators do a fine job, I find it easier to keep track of the characters and threads when I can see it in print. If you are someone that can’t understand a story well until you’ve heard it, go for the audio, or best of all, get both.

Highly recommended.

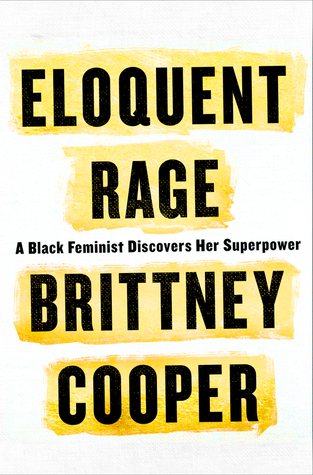

Cooper has had enough, and who can blame her?

Cooper has had enough, and who can blame her? Ta-Nehisi Coates is pissed. He has a thing or two to say about the historical continuity of racism in the USA, and in this series of eight outstanding essays, he says it well. I read it free and early thanks to Net Galley and Random House, and I apologize for reviewing it so late; the length wasn’t a problem, but the heat was hard to take. That said, this is the best nonfiction civil rights book I have seen published in at least 20 years.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is pissed. He has a thing or two to say about the historical continuity of racism in the USA, and in this series of eight outstanding essays, he says it well. I read it free and early thanks to Net Galley and Random House, and I apologize for reviewing it so late; the length wasn’t a problem, but the heat was hard to take. That said, this is the best nonfiction civil rights book I have seen published in at least 20 years. A hard look at the American penal system–from cops, to court, to prison–is past due, and within this scholarly but crystal-clear series of essays, the broken justice system that still rules unequally over all inside USA borders is viewed under a bright light. Isn’t it about time? Thank you to Doubleday and Net Galley for the DRC. It’s for sale, and anyone with an interest in seeing change should read it. Caucasian readers that still can’t figure out why so many African-Americans are so upset should buy this book at full price, and they should read it twice. If you read this collection and still don’t understand why most Civil Rights advocates are calling out that Black Lives Matter, it likely means you didn’t want to know. But bring your literacy skills when you come; well documented and flawless in both reason and presentation, it’s not a book that individuals without college-ready reading skills will be able to master.

A hard look at the American penal system–from cops, to court, to prison–is past due, and within this scholarly but crystal-clear series of essays, the broken justice system that still rules unequally over all inside USA borders is viewed under a bright light. Isn’t it about time? Thank you to Doubleday and Net Galley for the DRC. It’s for sale, and anyone with an interest in seeing change should read it. Caucasian readers that still can’t figure out why so many African-Americans are so upset should buy this book at full price, and they should read it twice. If you read this collection and still don’t understand why most Civil Rights advocates are calling out that Black Lives Matter, it likely means you didn’t want to know. But bring your literacy skills when you come; well documented and flawless in both reason and presentation, it’s not a book that individuals without college-ready reading skills will be able to master.