Morris considers DuBois the father of American sociology, and Morris is right. This is, of course, not the first time a Black man was robbed of credit for an accomplishment that was instead credited to a Caucasian American. It happens all the time. But until I ran across this scholarly study, I hadn’t thought about DuBois and sociology because I had never studied the latter. As an admirer of DuBois’ historical and political role, I was drawn to this book when I found it on Net Galley. Thank you to that excellent site as well as University of California Press for the DRC, which I was given in exchange for an honest review.

Morris considers DuBois the father of American sociology, and Morris is right. This is, of course, not the first time a Black man was robbed of credit for an accomplishment that was instead credited to a Caucasian American. It happens all the time. But until I ran across this scholarly study, I hadn’t thought about DuBois and sociology because I had never studied the latter. As an admirer of DuBois’ historical and political role, I was drawn to this book when I found it on Net Galley. Thank you to that excellent site as well as University of California Press for the DRC, which I was given in exchange for an honest review.

It is available for purchase now.

DuBois was a venerable intellectual, an academic light years ahead of most Americans of any racial or ethnic background. He was the first Black man to graduate from Harvard University, and in addition to his graduate work there, he also studied in Berlin under such luminaries as Max Weber and others. In Europe, he was treated as an equal by those he studied with, and I found myself wondering a trifle sadly—for him, not for us in the USA—why he chose to return here. And the answer is so poignant, so sweetly naïve, that I wanted to sit down and cry when I found it. Because once he had the empirical facts with which to debunk the whole US-Negro-inferiority mis-school of mis-thought, he genuinely believed he would be able to elevate African-Americans to a state of equality in the USA by laying out the facts. The racists that created Jim Crow laws in the south and an unofficial state of cold racism that let Black folk in the Northern states know where they were welcome and where they were not, would surely roll away, he thought, if he could reasonably haul out his charts, his graphs, his statistics, and demonstrate flawlessly, once and for all, that discrimination against Black people was based on incorrect information.

See what I mean? I could just cry for him.

So although DuBois was the first American to go to Europe, study sociology, and return with more and better credentials than any American academic, he could not persuade anyone with authority to bring about change, was not even allowed to present his findings to anybody except Black people in traditional Black colleges, because another school of sociologists, the Chicago school, were busy promoting armchair theories based on little data, or bogus data, all showing that Black people simply were not smart enough to become professionals or take on anything above and beyond manual labor, and of course, he was Black, so he must not be that smart, right?

Pause to allow your primal scream. It’s galling stuff.

Caucasian professors in Chicago had done a bit of reading, and with regard to Black people, decided that their craniums were too small to hold enough brain-iums. And just as there is one reactionary in every crowd that the newspapers will flock to in order to show that there is across-the-board agreement, so did Booker T Washington stand before any crowd that would listen to him (and the white academics just loved him), in order to say that it was the truth, that it was going to be a long time before the Negro was “ready” to do the difficult tasks involving critical thinking that had been so long denied him. Tiny steps; patience; tiny steps. Meanwhile, he extolled his fellow Black Americans to enroll their sons and daughters in programs teaching “industrial education”, so that they would be ready to do manual labor and put food on their families’ tables.

All of the studies that backed this line of thinking were deductive, starting with the answer (inferior beings, manual labor) and then finding the questions to fit that answer. DuBois had done inductive research because he was searching for information rather than looking for a rational-sounding way to keep a group of people entrenched in an economic underclass.

DuBois made the connection between the socialist theory he had studied and the material evidence before him: there were people getting rich off the backs of dark-skinned people, and they had a vested interest in maintaining Black folk as an underclass. Ultimately, he turned to political struggle, and that is how I knew about him, not as a sociologist, but as a Marxist. He also became the father of the interdisciplinary field of African-American studies. He helped found the NAACP.

This scholarly work, like just about anything produced by a university press, is not light reading. Rather, the author presents his thesis and synopsis, and then carefully, brick by brick, starts back at the beginning to build his case. His documentation is flawless, and his sources are diverse and strong. There is some repetition in the text, but that is appropriate in this type of writing. He is not there to entertain the reader, but to provide an authentic piece of research that will stand the test of time, so there is a little bit of a house-that-jack-built quality to the prose.

For serious admirers of DuBois’s work, this will be an excellent addition to your library. For those interested in sociology as a field, this is for you, too. And to those with a literacy level that permits you to access college-level material and who have a strong interest in African-American history and/or civil rights, this is a must-read.

For these readers, I recommend, in addition, The Souls of Black Folk, which I had not regarded as sociology-based material until now, though I have read it twice; and a collection of speeches by DuBois, which I have been intending to review for some time, and which will soon grace this page of my blog.

Morris has done outstanding work, and I like to think that if DuBois were here, he would be proud to see it.

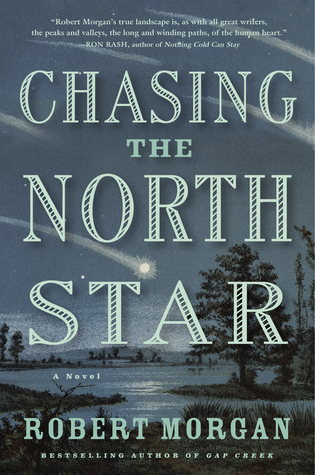

Chasing the North Star is a compelling narrative of two teenagers escaped from slavery on their flight toward the North. Thank you to Net Galley and Algonquin Books for the DRC, which I received in exchange for an honest review. This book becomes available to the public April 5, 2016.

Chasing the North Star is a compelling narrative of two teenagers escaped from slavery on their flight toward the North. Thank you to Net Galley and Algonquin Books for the DRC, which I received in exchange for an honest review. This book becomes available to the public April 5, 2016.