“White supremacy is not a marginal ideology. It is the early build of the country. It is a foundation on which the social edifice rises, bedrock of institutions. White supremacy also lies on the floor of our minds. Whiteness is not a deformation of thought, but a kind of thought itself…

‘The story that follows is not that a writer discovers a shameful family secret and turns to the public to confess it. The story here is that whiteness and its tribal nature are normal, everywhere, and seem as permanent as the sunrise.”

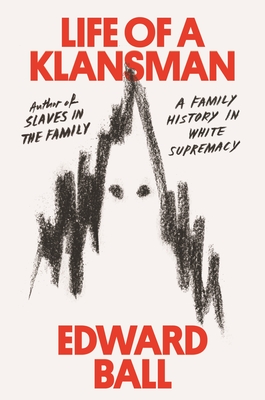

I read this book free and early; thanks go to Net Galley and Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux for the review copy.

Edward Ball writes about his ancestor, Constant Lecorgnes, known fondly within his family as “our Klansman.” The biography is noteworthy in that it is told without apology or moral judgement, as if Ball wants whites to feel okay about the racism, the rape, the exploitation, the murders, the terrorism that membership in the Ku Klux Klan, the Knights of the White Camellia, and any and all of the other white supremacist organizations have carried out, and will continue to carry out, in the United States. Relax, he tells us, it’s normal.

Well, let’s back up a moment. The “us” in the narrative is always Caucasians. It apparently hasn’t occurred to him that anybody else might read his book. In some ways, the “us” and the “our” used consistently and liberally throughout this biography are even worse than the explicit horrors detailed within its pages. It’s as if there is a huge, entitled club, and those that don’t belong are not invited to read. Further, it’s as if all white people are of a similar mind and share similar goals.

Not so much.

Ball won the National Book Award some years back for Slaves in the Family, a title currently adorning my shelves downstairs. I have begun it two or three times, but it didn’t hold me long enough for me to see what he does with it. And this book is the same, in that the late Lecorgnes is not particularly compelling as a subject, except within the framework of his terrorism. He was not, Ball tells us, a key player; he was just one more Caucasian foot soldier within the Klan. And so, the reading drones along, and then there are the key pronouns that capture my attention, those that give ownership to his terrible heritage, and a couple of paragraphs of the history of the period, particularly within Southern Louisiana, follow; lather, rinse, repeat.

As I read, I searched for accountability. As it happens, I have one of those relatives too; but my elders, though not beacons within the Civil Rights realm by a long shot, understood that such a membership brings shame upon us, and consequently I was not supposed to know about him at all. I overheard some words intended to be private, uttered quietly during a moment of profound grief following a sudden death. My mother spoke to someone—my father? I can’t recall—but she referred to her father’s horrifying activity, and I was so shocked that I left off lurking and spying, and burst into the room. I believe I was ten years old at the time. I was told that the man—who was never, and never will be referred to in the fond, familiar manner that Ball does—was not entirely right in the head. He truly believed he was helping to protect Southern Caucasian women, but he was wrong. It was awful, and now it’s over; let’s not talk about it anymore. In fact, this topic was so taboo that my own sister didn’t know. She is old now, and was shocked when I mentioned it last spring. She had no idea.

As I developed, I understood, from teachers and friends more enlightened than Mr. Ball, that the best way we can deal with ugly things in our background that we cannot change, is to contribute our own energies in the opposite direction. I’ve lived by it, and so I was waiting for Ball to say something similar, if not in the prologue, then surely somewhere near the end; but he never did. If Ball feels any duty whatsoever to balance the scales of his family’s terrible contribution, he doesn’t offer it up. There’s no call to action, no cry for social justice. Just the message that hey—it’s normal, and it’s fine.

I’m not sure if I want to read his other work anymore; but I know that what I cannot do, and will not do, is recommend this book to you.