History buffs rejoice; the definitive Nixon biography is here. John A. Farrell is the renowned biographer of Clarence Darrow. Now he gives us a comprehensive, compelling look at the only US president ever to resign from office under the cloud of imminent impeachment. This is the only Nixon biography that answers the many questions that left Americans—and those around the world that were watching—scratching our heads. Why, why, and why would he do these things? Farrell tells us. I read this book free and in advance, thanks to Net Galley and Doubleday, but it would have been worth paying the full retail price if I’d had to. It’s available to the public now.

History buffs rejoice; the definitive Nixon biography is here. John A. Farrell is the renowned biographer of Clarence Darrow. Now he gives us a comprehensive, compelling look at the only US president ever to resign from office under the cloud of imminent impeachment. This is the only Nixon biography that answers the many questions that left Americans—and those around the world that were watching—scratching our heads. Why, why, and why would he do these things? Farrell tells us. I read this book free and in advance, thanks to Net Galley and Doubleday, but it would have been worth paying the full retail price if I’d had to. It’s available to the public now.

Anytime I read nonfiction, I start with the sources. If the author hasn’t verified his information using primary sources, I go no further. Nonfiction is only fact if the author can prove that what he says is true—and I have never seen more meticulous, more thorough source work than what I see here. Every tape in the Nixon library; every memoir, from Nixon’s own, to those of the men that advised him as president, to those written by his family members, to those that opposed him are referenced, and that’s not all. Every set of presidential papers from Eisenhower on forward; the memoirs of LBJ, the president that served before Nixon took office; reminiscences of Brezhnev, leader of Russia ( which at the time was part of the USSR); reminiscences of Chinese leaders that hosted him; every single relevant source has been scoured and referenced in methodical, careful, painstaking detail. Farrell backs up every single fact in his book with multiple, sometimes a dozen excellent sources.

Because he has been so diligent, he’s also been able to take down some myths that were starting to gain a foothold in our national narrative. An example is the assertion that before the Kennedys unleashed their bag of dirty tricks on Nixon’s campaign in 1960, Nixon was a man of sound principle and strong ethics. A good hard look at his political campaigns in California knocks the legs out from under that fledgling bit of lore and knock it outs it out of the nest, and out of the atmosphere. Gone!

Lest I lend the impression that this is a biography useful only to the most careful students of history, folks willing to slog endlessly through excruciating detail, let me make myself perfectly clear: the man writes in a way that is hugely engaging and at times funny enough to leave me gasping for air. Although I taught American history and government for a long time, I also learned a great deal, not just about Nixon and those around him, but bits and pieces of American history that are relevant to the story but that don’t pop up anywhere else.

For those that have wondered why such a clearly intelligent politician, one that would win by a landslide, would hoist his own petard by authoring and authorizing plans to break into the offices of opponents—and their physicians—this is your book. For those that want to know what Nixon knew and when he knew it, this is for you, too.

I find myself mesmerized by the mental snapshots Farrell evokes: a tormented Nixon, still determined not to yield, pounding on the piano late into the night. I hear the clink of ice cubes in the background as Nixon, talking about Prime Minister Indira Gandhi of India, suggests that “The Indians need—what they really need—is a mass famine.”

I can see Kissinger and the Pentagon making last minute arrangements to deal with a possible 11th hour military coup before Nixon leaves office. Don’t leave him with the button during those last 24 hours, they figure.

And I picture poor Pat, his long-suffering wife to whom he told nothing, nothing, nothing, packing all through the night before they are to leave the White House…because of course he didn’t tell her they were going home in time to let her pack during normal hours.

The most damning and enlightening facts have to do with Vietnam and particularly, Cambodia. Farrell makes a case that the entire horrific Holocaust there with the Khmer Rouge and Pol Pot could have been avoided had Nixon not contacted the Vietnamese ambassador and suggested that he not make a deal with Johnson to end the war.

Whether you are like I am, a person that reads every Watergate memoir that you can obtain free or cheaply, or whether you are a younger person that has never gone into that dark tunnel, this is the book to read. It’s thorough and it’s fair, and what’s more, it’s entertaining.

Get it. Read it. You won’t be sorry!

Dorothy Day is an interesting historical figure, the woman that founded The Catholic Worker, which was initially a combined newspaper, homeless shelter, and soup kitchen. I once subscribed to The Catholic Worker, and since it cost one penny per issue, you couldn’t beat the price. I saw this biography available and snapped it up from Net Galley; thanks go to them and Scribner, who provided me with a DRC in exchange for an honest review. This title was published in late January and is now available for purchase.

Dorothy Day is an interesting historical figure, the woman that founded The Catholic Worker, which was initially a combined newspaper, homeless shelter, and soup kitchen. I once subscribed to The Catholic Worker, and since it cost one penny per issue, you couldn’t beat the price. I saw this biography available and snapped it up from Net Galley; thanks go to them and Scribner, who provided me with a DRC in exchange for an honest review. This title was published in late January and is now available for purchase. The American Civil War is part of the curriculum I used to teach, and in retirement I still enjoy reading about it. When I saw that Open Road Media had listed this title on Net Galley to be republished digitally this summer, I swooped in and grabbed a copy for myself. I was so eager to read it that I bumped it ahead of some other DRCs I already had, and I really wanted to like it. Unfortunately, this is a shallow effort and it shows. Don’t buy it for yourself, and for heaven’s sake don’t advise your students to read it.

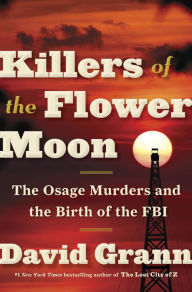

The American Civil War is part of the curriculum I used to teach, and in retirement I still enjoy reading about it. When I saw that Open Road Media had listed this title on Net Galley to be republished digitally this summer, I swooped in and grabbed a copy for myself. I was so eager to read it that I bumped it ahead of some other DRCs I already had, and I really wanted to like it. Unfortunately, this is a shallow effort and it shows. Don’t buy it for yourself, and for heaven’s sake don’t advise your students to read it. I received this book free from Net Galley, courtesy of Doubleday, in exchange for an honest review. It looked like a fascinating read, but I am disturbed by the sources chosen, which sent up all sorts of red flags right from the get-go and before I had even focused on the references themselves, a due diligence that has to be done before any nonfiction work can be recommended. Once I examined the references, I concluded that so many of them are so questionable that nobody, including the writer, can demonstrate anything beyond the premise of the book itself to be true. The killings happened; that’s about it.

I received this book free from Net Galley, courtesy of Doubleday, in exchange for an honest review. It looked like a fascinating read, but I am disturbed by the sources chosen, which sent up all sorts of red flags right from the get-go and before I had even focused on the references themselves, a due diligence that has to be done before any nonfiction work can be recommended. Once I examined the references, I concluded that so many of them are so questionable that nobody, including the writer, can demonstrate anything beyond the premise of the book itself to be true. The killings happened; that’s about it. John Dean was counsel to the president during the Nixon administration, and was the first to testify against all of the Watergate conspirators, including Nixon and including himself, a bold but necessary decision that led to Nixon’s resignation—done to avoid imminent impeachment—and Dean’s imprisonment. Dean’s story is a real page turner, and Nixon-Watergate buffs as well as those that are curious about this time period should read this book. I read the hard copy version, for which I paid full jacket price, shortly after its release, and when I saw that my friends at Open Road Media and Net Galley were re-releasing it digitally, I climbed on board right away. This title is available for sale today, December 20, 2016.

John Dean was counsel to the president during the Nixon administration, and was the first to testify against all of the Watergate conspirators, including Nixon and including himself, a bold but necessary decision that led to Nixon’s resignation—done to avoid imminent impeachment—and Dean’s imprisonment. Dean’s story is a real page turner, and Nixon-Watergate buffs as well as those that are curious about this time period should read this book. I read the hard copy version, for which I paid full jacket price, shortly after its release, and when I saw that my friends at Open Road Media and Net Galley were re-releasing it digitally, I climbed on board right away. This title is available for sale today, December 20, 2016. What is it about mobsters that draws our attention? National Book Award winner Deirdre Bair takes on America’s most famous mobster, Al Capone, and examines the myths and legends that have sprung up in the time since his death. I thank Net Galley and Doubleday for permitting me the use of a DRC, which I received free in exchange for this honest review. The book is available to purchase now.

What is it about mobsters that draws our attention? National Book Award winner Deirdre Bair takes on America’s most famous mobster, Al Capone, and examines the myths and legends that have sprung up in the time since his death. I thank Net Galley and Doubleday for permitting me the use of a DRC, which I received free in exchange for this honest review. The book is available to purchase now. I was fortunate to receive a DRC of this two volume biography of America’s greatest general, US Grant. Thanks go to Open Road Media and Net Galley for providing it in exchange for this honest review. This is the sixth Grant biography I’ve read, and aside possibly from Grant’s own memoirs, which are valuable in a different way than this set, I have to say this is hands-down the best I have seen. Catton won the Pulitzer for one of his civil war trilogies, and this outstanding biography is in the same league. Those with a serious interest in the American Civil War or military history in general should get it. It’s available for purchase now.

I was fortunate to receive a DRC of this two volume biography of America’s greatest general, US Grant. Thanks go to Open Road Media and Net Galley for providing it in exchange for this honest review. This is the sixth Grant biography I’ve read, and aside possibly from Grant’s own memoirs, which are valuable in a different way than this set, I have to say this is hands-down the best I have seen. Catton won the Pulitzer for one of his civil war trilogies, and this outstanding biography is in the same league. Those with a serious interest in the American Civil War or military history in general should get it. It’s available for purchase now. In Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe, Robert Matzen provides an engaging, compelling memoir that focuses primarily on Stewart’s time as an aviator during World War II. Thanks go to Net Galley and to Goodknight Books for the DRC, which I read free in exchange for this honest review.

In Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe, Robert Matzen provides an engaging, compelling memoir that focuses primarily on Stewart’s time as an aviator during World War II. Thanks go to Net Galley and to Goodknight Books for the DRC, which I read free in exchange for this honest review. Nagy does a more than serviceable job in documenting Washington’s intelligence methods. Thank you for the DRC, which I received free in exchange for an honest review from Net Galley and St. Martin’s Press. This title is for sale today.

Nagy does a more than serviceable job in documenting Washington’s intelligence methods. Thank you for the DRC, which I received free in exchange for an honest review from Net Galley and St. Martin’s Press. This title is for sale today. If I were to review the subject of this memoir rather than the book itself, it would be a slam-dunk five star rating. As it is, I can still recommend Carmon’s brief but potent biography as the best that has been published about this fascinating, passionate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. I have no doubt many more will follow, and it’s possible I will read every one of them. As it stands, this is a rare instance in which I turned my back on my pile of free galleys long enough to ferret this gem out at the Seattle Public Library, because I just had to read it. You should too.

If I were to review the subject of this memoir rather than the book itself, it would be a slam-dunk five star rating. As it is, I can still recommend Carmon’s brief but potent biography as the best that has been published about this fascinating, passionate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. I have no doubt many more will follow, and it’s possible I will read every one of them. As it stands, this is a rare instance in which I turned my back on my pile of free galleys long enough to ferret this gem out at the Seattle Public Library, because I just had to read it. You should too.