Elie Metchnikoff is credited with several medical discoveries, some of which were found before Mother Russia was entirely ready to receive them. This interesting though technically challenging text is the story of his life, and especially of his scientific career and achievements. Thank you Net Galley and Chicago Review Press for the DRC, which I received in exchange for an honest review. This title will be available to the public April 1, 2016.

Elie Metchnikoff is credited with several medical discoveries, some of which were found before Mother Russia was entirely ready to receive them. This interesting though technically challenging text is the story of his life, and especially of his scientific career and achievements. Thank you Net Galley and Chicago Review Press for the DRC, which I received in exchange for an honest review. This title will be available to the public April 1, 2016.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, Russia still had a tsar—a royal ruler with power similar to that of an emperor—and it still had serfs, who legally could not leave the plots of land assigned to them to farm for the benefit of royal landowners. It was not an ideal climate for science or any other aspect of enlightened thinking, but Metchnikoff was not only gifted, he was immeasurably stubborn, and by such methods as posing as a college student in order to sneak into lectures, he achieved an excellent education and began to pave new inroads toward discovering how the human immune system works.

His theory that cells in the human body swarm around and dispose of microbes that enter the body in order to kill germs was true, but proving it to those with authority in Russia was not an easy thing to do. Only recently had germs been discovered to cause disease; not so long before, it was assumed that God smote certain people or their loved ones in retribution for their bad behavior or thoughts. Being a scientist in such a place was challenging, and eventually, after being snubbed repeatedly by the German academics he sought to win over, Metchnikoff found his way to Paris, and the Pasteur Institute, where he would spend the bulk of his career.

His refusal to participate in elitist cliques that feasted on 8 course gourmet meals while half of London starved warmed my heart, as did his refusal to be roped into other social pretensions. Really, in another time and place, this would be my kind of guy.

Here I must disclose the fact that the sciences are not my forte. Only since retirement from teaching in the humanities have I found the time and confidence to explore memoirs of famous scientists. Last autumn I read and reviewed the biography of Dr. Bennet Omalu, the man that discovered a brain disease that was the result of repeated blows to the head consistent with American football. Cheered by my success in understanding and reviewing that fascinating story, I decided to tackle this one…with less satisfactory results.

I have never been good at understanding science. It’s that simple.

So if science and in particular the history of immunology or disease is your wheelhouse, this may be a four or five star read for you. But although I am not scientifically minded, I do have a sturdier education than the average American, and so I think I’m being fair in saying that the average reader-on-the-street that picks this up due to general interest rather than exceptional training may find it to be a great deal of work.

I did check the endnotes; I always do. So unless the author has simply invented a lot of sources in other languages than English—which seems very unlikely indeed—then I can safely say that this author has relied primarily on sources that the average English-speaking reader will not be able to tap into. Strong documentation from a wide variety of sources.

Recommended to those with a higher than average facility for matters of science, and for those interested enough to wrestle with challenging material.

Huge thanks go to Net Galley and University of California Press, who provided me with a DRC in exchange for an honest review. It has taken me some time to read and rate it because once I had the DRC for Volume 3, I decided I should hunt down volumes 1 and 2 and read those first. Now I am finally finished, and it was well worth the effort.

Huge thanks go to Net Galley and University of California Press, who provided me with a DRC in exchange for an honest review. It has taken me some time to read and rate it because once I had the DRC for Volume 3, I decided I should hunt down volumes 1 and 2 and read those first. Now I am finally finished, and it was well worth the effort. I received this DRC free in exchange for an honest review. Thanks go to Net Galley and Open Road Integrated Media for letting me read it; Donald won the Pulitzer for his Lincoln biography, and I was sure this series of essays written for the purpose of dismantling myths surrounding the most revered president ever to occupy the White House would be hidden treasure rediscovered. What a crushing disappointment.

I received this DRC free in exchange for an honest review. Thanks go to Net Galley and Open Road Integrated Media for letting me read it; Donald won the Pulitzer for his Lincoln biography, and I was sure this series of essays written for the purpose of dismantling myths surrounding the most revered president ever to occupy the White House would be hidden treasure rediscovered. What a crushing disappointment. What, another one? Yes friends, every time I find a noteworthy biography of Grant, it leads me to another. This is not a recent release; I found it on an annual pilgrimage to Powell’s City of Books in my old hometown, Portland, Oregon. I always swing through the American Civil War shelves of their history section, and I make a pass through the military history area as well. I found this treasure, originally published in 2001 when I was too busy to read much of anything. It was a finalist for the Pulitzer; A New York Times and American Library Association Notable Book; and Publishers Weekly Book of the Year. But in choosing a thick, meaty biography such as this one—it weighs in at 781 pages, of which 628 are text, and the rest end-notes and index—I always skip to the back of the book and skim the sources. If a writer quotes other secondary texts at length, I know I can skip the book in my hand and search instead for those the writer has quoted. But Smith quotes primary documents, dusty letters, memos, and military records for which I would have to load my wide self into the car and drive around the country to various libraries in out of the way places. Source material like Smith’s is promising, so I bought a gently used copy for my own collection and brought it on home. And unlike the DRC’s I so frequently read at a feverish pace in order to review them by a particular date, I took my time with this one, knowing that if I only read a few pages each day and then reflected on them before moving on, I would retain more.

What, another one? Yes friends, every time I find a noteworthy biography of Grant, it leads me to another. This is not a recent release; I found it on an annual pilgrimage to Powell’s City of Books in my old hometown, Portland, Oregon. I always swing through the American Civil War shelves of their history section, and I make a pass through the military history area as well. I found this treasure, originally published in 2001 when I was too busy to read much of anything. It was a finalist for the Pulitzer; A New York Times and American Library Association Notable Book; and Publishers Weekly Book of the Year. But in choosing a thick, meaty biography such as this one—it weighs in at 781 pages, of which 628 are text, and the rest end-notes and index—I always skip to the back of the book and skim the sources. If a writer quotes other secondary texts at length, I know I can skip the book in my hand and search instead for those the writer has quoted. But Smith quotes primary documents, dusty letters, memos, and military records for which I would have to load my wide self into the car and drive around the country to various libraries in out of the way places. Source material like Smith’s is promising, so I bought a gently used copy for my own collection and brought it on home. And unlike the DRC’s I so frequently read at a feverish pace in order to review them by a particular date, I took my time with this one, knowing that if I only read a few pages each day and then reflected on them before moving on, I would retain more. The Man Who Cried I Am was originally published during the turmoil of the late 1960’s, in the throes of the Civil Rights and antiwar movements, and following the assassinations of President Kennedy, his brother Bobby, Martin Luther King Junior, and Malcolm X. Now we find ourselves in the midst of a long-overdue second civil rights movement, and this title is published again. We can read it digitally thanks to Open Road Integrated Media. I was invited to read it by them and the fine people at Net Galley. I read it free in exchange for an honest review. It is available for purchase now.

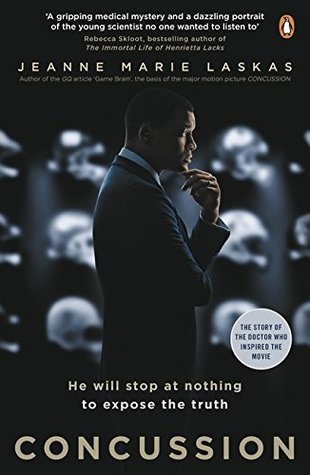

The Man Who Cried I Am was originally published during the turmoil of the late 1960’s, in the throes of the Civil Rights and antiwar movements, and following the assassinations of President Kennedy, his brother Bobby, Martin Luther King Junior, and Malcolm X. Now we find ourselves in the midst of a long-overdue second civil rights movement, and this title is published again. We can read it digitally thanks to Open Road Integrated Media. I was invited to read it by them and the fine people at Net Galley. I read it free in exchange for an honest review. It is available for purchase now. You don’t have to enjoy football to appreciate Concussion, the riveting new biography of Bennet Omalu, the Nigerian neurological pathologist that discovered CTE, a type of permanent brain damage caused by repetitive concussions, such as that experienced by football players. Not only the content, but the engaging voice with which it is told, make it worth everyone’s while. I was fortunate enough to read it free, courtesy of Net Galley and Random House, but when it comes out Tuesday, November 24, I recommend you get a copy for yourself. It’s information everyone really ought to have, especially those that play American football, or have family members that do.

You don’t have to enjoy football to appreciate Concussion, the riveting new biography of Bennet Omalu, the Nigerian neurological pathologist that discovered CTE, a type of permanent brain damage caused by repetitive concussions, such as that experienced by football players. Not only the content, but the engaging voice with which it is told, make it worth everyone’s while. I was fortunate enough to read it free, courtesy of Net Galley and Random House, but when it comes out Tuesday, November 24, I recommend you get a copy for yourself. It’s information everyone really ought to have, especially those that play American football, or have family members that do.