Second Daughter is historical fiction based on the true story of an enslaved woman that went to court and won her freedom in New England around the time of the American Revolution. I received this DRC free from Net Galley and Open Road Integrated Media in exchange for an honest review. And it’s just as well, because if I had paid any money at all for this brief but troubled book, I would be deeply unhappy.

Second Daughter is historical fiction based on the true story of an enslaved woman that went to court and won her freedom in New England around the time of the American Revolution. I received this DRC free from Net Galley and Open Road Integrated Media in exchange for an honest review. And it’s just as well, because if I had paid any money at all for this brief but troubled book, I would be deeply unhappy.

First, let’s examine the positive aspects that allowed the second star to happen. Walter has nailed setting, and when Aissa, the girl that serves as our narrator, describes the kitchen of her master’s house, we are there and can see it all. Here she does an excellent job. Other settings are also well told.

Second, the length, just 119 pages, is accessible for young adult readers, many of whom find it difficult, in these technologically advanced times, to focus all the way through a full length novel.

Unfortunately, the problems outweigh the virtues. I have two issues that plant this story on my literary wall of shame. The first is technical, the second philosophical.

Technically I see this as a decent if unmemorable read, and were I to judge this strictly on the writer’s skill, I would call this a three star novel. Overlong passages of narrative, often unbroken by action or dialogue and in lengthy paragraphs, are likely to hit the average adolescent’s snooze button early on. The choice to tell everything in past tense as opposed to the more widely used literary present deadens the pace further. When we finally do get a passage of dialogue, it is so stiff and stilted that not even the most engaging teacher, when reading this out loud to her class, could possibly breathe life into it. One character is depicted as speaking with a Sambo-like dialect, all “dis” and “dat”. If one is going to use a dialect, make it respectful and readable. This verges on mimicry, and any Black students in the room that haven’t tuned out or gone to sleep yet are going to be pissed, and rightly so.

I can see that Walters meant well in writing from the point of view of a Black slave girl and in depicting a victory gained by Black people on their own behalf, as opposed to the usual torture, death, and despair that represented those kidnapped and forced into slavery. But this is also where I have to step back and ask what the ultimate effect of this book will be on students that read it.

For the average or below average middle school student, reading all the way through even a fairly brief novel such as this one will likely be the only book they make it through during the term in which slavery is covered in the social studies, humanities, or language arts/social studies block. Part of the power of good literature—which this isn’t, and in some ways that may be for the better—is that it drives home a central message. I can envision students that pay attention to this book, perhaps because the teacher is particularly engaging and has driven home its importance, and then walking away from the term’s work convinced that all any slave in any part of the USA ever had to do to get out of his or her predicament was to find a good attorney, take the matter to court, and bang, that’s it, we’re free. Let’s party.

This novel addresses a relatively brief period in the northern states, where slavery had been legal but had not been as widespread as in the Southern states. King Cotton had not become the dominant economic mover it would become by 1850, when its grip on all of US governmental institutions would be absolute. By then, northerners made their money indirectly from the cotton industry in everything from shipping, boat building, rope making, and banking to growing crops for consumption by Southerners and in some cases, for their slaves.

If one is going to teach about slavery, far better to do so as part of an American Civil War unit. It’s a tender, sensitive, painful thing for children of color, but it’s not okay to deceive them, however unintentionally, with the misimpression that all slaves had options that they didn’t. Better to use portions of Alex Haley’s Roots; teach about the vast but much-ignored free Black middle class in the north that was the primary moving force behind the Underground Railroad; or to show the movie “Glory” in class to emphasize the positive, powerful things that African-American people did during this revolutionary time, than to emphasize something as obscure, limited, and potentially misleading as what Walter provides here.

I am trying to think of instances in which this book might be part of a broader, more extensive curriculum such as the home-schooling of a voracious young reader, yet even then I find myself back at the technical aspect, which results in a book that is dull, dull, dull. Literature should engage a student and cause him or her to reach for more, rather than make students wonder if it will ever end.

In general I have resolved to read fewer YA titles than when I was teaching and treat myself to more advanced work during my retirement. I made an exception for this title because the focus appeared to be right in my wheelhouse, addressing US slavery and the civil rights of Black folk in America. I regret doing so now, but it doesn’t have to happen to you too.

Save yourself while there’s time. Read something else. And for heaven’s sake, don’t foist this book on kids.

I read this memoir, one of the most important of our era, before I was writing reviews. I bought it in the hard cover edition, because I knew I would want it to last a long time and be available to my children and their children. It was worth every nickel. It’s lengthy and requires strong literacy skills and stamina, but if you care about social justice and are going to pull out all the stops for just one hefty volume in your lifetime, make it this one.

I read this memoir, one of the most important of our era, before I was writing reviews. I bought it in the hard cover edition, because I knew I would want it to last a long time and be available to my children and their children. It was worth every nickel. It’s lengthy and requires strong literacy skills and stamina, but if you care about social justice and are going to pull out all the stops for just one hefty volume in your lifetime, make it this one. Sometimes people say they “ran across” a book, and that is close to how I came to read James Lee Burke for the first time. I had been tidying up for company, and my daughter had selected this book from the “free” pile at school, then decided she didn’t want it. She is a teenager, so instead of finding our charity box and putting it there, she dropped it on the upstairs banister. I scooped it up in irritation..then looked at it again. Flipped it over…read the blurb about the writer. This man is a rare winner of TWO Edgars. Really? I examined the title again; I hadn’t read any novels based on Hurricane Katrina, so why not give it a shot?

Sometimes people say they “ran across” a book, and that is close to how I came to read James Lee Burke for the first time. I had been tidying up for company, and my daughter had selected this book from the “free” pile at school, then decided she didn’t want it. She is a teenager, so instead of finding our charity box and putting it there, she dropped it on the upstairs banister. I scooped it up in irritation..then looked at it again. Flipped it over…read the blurb about the writer. This man is a rare winner of TWO Edgars. Really? I examined the title again; I hadn’t read any novels based on Hurricane Katrina, so why not give it a shot? Had this story not received such wide acclaim and been made into a movie (which I’ve yet to see, but I watched the Oscars), I would probably never have gone near it. I like working class protagonists, and I don’t read many romances, because often as not, they are corny, soft porn, or both. But I saw it at the library and decided to give it a try, and I quickly remembered, upon reading it, that some rules are made to be broken. So even if you usually don’t read romances, and even if a retired British pensioner is not your idea of an interesting protagonist, this should be the exception to the rule.

Had this story not received such wide acclaim and been made into a movie (which I’ve yet to see, but I watched the Oscars), I would probably never have gone near it. I like working class protagonists, and I don’t read many romances, because often as not, they are corny, soft porn, or both. But I saw it at the library and decided to give it a try, and I quickly remembered, upon reading it, that some rules are made to be broken. So even if you usually don’t read romances, and even if a retired British pensioner is not your idea of an interesting protagonist, this should be the exception to the rule. Chasing the North Star is a compelling narrative of two teenagers escaped from slavery on their flight toward the North. Thank you to Net Galley and Algonquin Books for the DRC, which I received in exchange for an honest review. This book becomes available to the public April 5, 2016.

Chasing the North Star is a compelling narrative of two teenagers escaped from slavery on their flight toward the North. Thank you to Net Galley and Algonquin Books for the DRC, which I received in exchange for an honest review. This book becomes available to the public April 5, 2016. I found this gem at my favorite used bookstore in Seattle, Magus Books, which is just a block from the University of Washington. Its strength, as the title suggests, is in tracing the story of the American Civil War as told by the cinema. Those interested in the way in which movie impacts both culture and education in the USA would do well to find this book and read it.

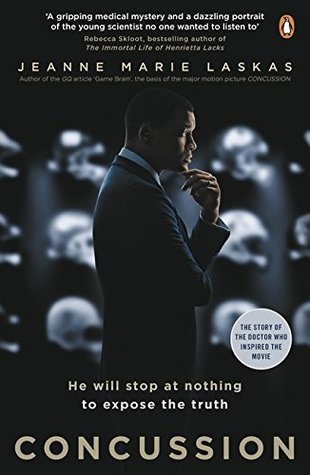

I found this gem at my favorite used bookstore in Seattle, Magus Books, which is just a block from the University of Washington. Its strength, as the title suggests, is in tracing the story of the American Civil War as told by the cinema. Those interested in the way in which movie impacts both culture and education in the USA would do well to find this book and read it. You don’t have to enjoy football to appreciate Concussion, the riveting new biography of Bennet Omalu, the Nigerian neurological pathologist that discovered CTE, a type of permanent brain damage caused by repetitive concussions, such as that experienced by football players. Not only the content, but the engaging voice with which it is told, make it worth everyone’s while. I was fortunate enough to read it free, courtesy of Net Galley and Random House, but when it comes out Tuesday, November 24, I recommend you get a copy for yourself. It’s information everyone really ought to have, especially those that play American football, or have family members that do.

You don’t have to enjoy football to appreciate Concussion, the riveting new biography of Bennet Omalu, the Nigerian neurological pathologist that discovered CTE, a type of permanent brain damage caused by repetitive concussions, such as that experienced by football players. Not only the content, but the engaging voice with which it is told, make it worth everyone’s while. I was fortunate enough to read it free, courtesy of Net Galley and Random House, but when it comes out Tuesday, November 24, I recommend you get a copy for yourself. It’s information everyone really ought to have, especially those that play American football, or have family members that do.