2.5 stars, rounded upwards.

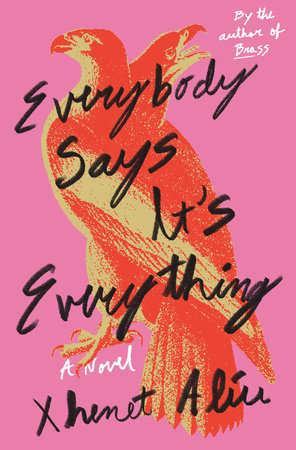

Xhenet (pronounced similar to “Jeanette”) Aliu is the author of Brass, the award-winning debut novel that was one of my favorites of 2018. When I saw that she had a new book, Everybody Says It’s Everything, I was so excited that I bounced up and down in my desk chair. My thanks go to Random House and NetGalley for the invitation to read and review; sadly, I found this book disappointing. The sophomore slump is real, friends.

Our story centers—to the extent that it has a center—on adopted twins, Drita and Pete, who’ve been leading quintessential American lives. Drita was a star student, and is in the midst of graduate studies when she is called home to care for her mother; Pete—actually Petrit—has been in various sorts of trouble, and now his girlfriend and son have landed with Drita looking for help, since they aren’t getting any from Pete. The story takes us through their native Albanian roots and heritage, through the war in Kosovo, and through Pete’s discouragement, hardship, and addiction.

I have a hard time connecting with any of these characters. The dialogue drags, and the poignant qualities that I found in Brass are nowhere to be found. Both are sad stories, but the protagonist in Brass had my whole heart and my full attention, whereas these characters left me feeling as if I was eavesdropping on one more group of depressed, underserved people, but also edging towards the door. I was just straight up bored, a word I rarely use in reviews. I continued all the way through because I was sure that it would turn brilliant any minute; it never did.

I look forward to seeing what this author writes next, because she has proven that she has the ability to connect with readers in general and me in particular, but I can’t recommend this book to you.