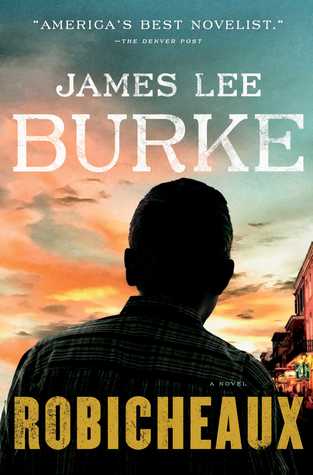

If you are new to the series, do yourself a favor and go all the way back. This book is #18 of 20. Start with The Neon Rain and work your way forward. You won’t be one bit sorry.

If you are new to the series, do yourself a favor and go all the way back. This book is #18 of 20. Start with The Neon Rain and work your way forward. You won’t be one bit sorry.

For those who wonder whether this remarkable author whose work began in the 1960’s still has the stuff it takes to write Edgar and Pulitzer-nominee worthy material, the fact is that if anything, he’s even better. He is one of a very small number of mystery and crime thriller authors that can juggle the bad guys and storyline that is related to the crime under investigation and weave them inextricably and seamlessly with the continuing story of friendship, of familial devotion, and of personal ethics. Besides Sue Grafton, I have never seen a mystery writer develop character more fully or completely without missing a beat, and do it in an ongoing manner over decades without any consistency popping up to remind us that time has passed and the author’s memory is imperfect. Either Burke has an amazing memory or an amazing editor; one way or the other, he is an unmatchable writer.

The Glass Rainbow finds Dave still living in his home in New Iberia with Molly, Snuggs, and that almost supernaturally long-lived raccoon, Tripod. Alafair is home from Reed College, and she is dating a very bad man. Kermit Abelard, the man Alafair has fallen for, has contacts in the literary world that Alafair has been told will help launch her career; but people like Robert Weingart and Layton Blanchet are not in the world to be guardian angels to the young, the naïve, or the vulnerable. In fact, the opposite is true:

“ Sex was not a primary issue in their lives. Money was. When it comes to money, power and sex are secondary issues. Money buys both of them, always.”

This gibes with what I also believe is true of the vast majority of very wealthy people, and that is one of the reasons Burke’s work resounds in such a personally satisfying way for me. But it’s really more than a philosophical affinity; it is also unmistakably about character development.

In many novels, whether they are mystery, historical fiction, or general literature, there are plot devices that pop up over and over and over again. A threat against the protagonist’s family member is as old as the mountains, and as tired as a traveling salesman who’s been on his feet for three weeks straight. In other words, I see it coming and I groan. Once in awhile, if the novel was already not going well, I abandon the book then and there.

Another is alcoholism. A lot of writers know that there are a tremendous number of recovering alcoholics, not to mention people who love them, among their readership. I can relate to it. There are so many drunks and former drunks in my family that I won’t even have hooch in my house. I am a single-household Carrie Nation. Get it out of here! But hell if I want to read about it. I am already sick of alcoholism, and I do not need it in my fiction. Do. Not.

Cancer is another one. I won’t rant. You get the idea.

But because Burke’s writing is so deeply personal, he can (and does) use all of those above devices at one point or another and sometimes I don’t even notice that I am accepting his premise until halfway into the book. During the first three books of his series, which he has said in interviews were a trilogy in which Robicheaux sorts out his alcoholism before he is good for much else, I got tired of it but I kept on turning the pages.

The magic that makes his writing so exceptional is that he draws the reader in deeply enough to persuade us, at least for portions of the time that we are reading his novel, that we are part of his family. Alafair is not just his daughter. She is part of our family. We have to watch out for her. The boomer generation reads this stuff, and a lot of us have raised teens and young adults who have made some mis-steps that either were dangerous or appeared to be, and we spent our fair share of sleepless nights, so when Dave rolls out of bed after failing to sleep and goes to sit in the kitchen until his newly-adult daughter shows up to home, we put on our bathrobes and trudge into the kitchen with him. We blink drowsily and pull up a chair. Or we follow him on out to the porch.

And we don’t like these people Alafair is hanging out with. When we get older, we become adept, often through cruel experience, at spotting the phony altruism that these people slide over their personas like cheap sparkling hubcaps with metallic spinners on an old jalopy. When Layton dies, Burke reflects to Clete:

“I think Layton was too greedy to kill himself. He was the kind of guy who clings to the silverware when the mortician drags him out of his home.”

Later, when trying to get a handle on Abelard and his involvement in a case to which Robicheaux has been assigned, he and Clete attend a charity gala:

“ The guests at the banquet and fundraiser were an extraordinary group. Batistianos from Miami were there, as well as friends of Anastasio Somoza. The locals, if they could be called that, were a breed unto themselves. They were porcine and sleek and combed and brushed, and they jingled when they walked.”

Later in the story one of them speaks down to Robicheaux, telling him that his working class roots are repugnant:

“You may have gone to college, Mr. Robicheaux, but you wear your lack of breeding like a rented suit.”

Hey. That’s not a rented suit. It’s his own damn suit, and he should wear it proudly.

And thus I find myself defending him as I might a brother, a cousin, an uncle. He’s not just one of the good guys; he’s one of my good guys.

Some reviewers say that Burke has a particular kind of book he writes that becomes redundant over time. I disagree. His Robicheaux series no more becomes redundant than a human life does. Is my sister’s personality, my cousin’s, my son’s and my daughter’s, consistent over time for the most part, though of course we all grow and evolve in certain ways? Oh yes yes yes. And am I tired of them? Do I feel as if I would prefer to move on to others who may be more full of surprises? Not in the least.

Just as we make new friends, I love reading new novelists, whether they are merely new to me, or just breaking into the field.

But there is nothing quite like an old friend or a beloved aunt; nobody and nothing can replace these.

And thus it is with the novels written by James Lee Burke.

“You ever hear of the Bobbsey Twins from homicide?”

“You ever hear of the Bobbsey Twins from homicide?” “Our ancestors were not wrong in their superstitions; there is reason to fear the dark.”

“Our ancestors were not wrong in their superstitions; there is reason to fear the dark.”