River of Earth, originally published in 1940, is a classic tale of Appalachian coal miners, dirt-poor, ever-proud people living deep in the mountains, crags and hollers, trying to scratch out a living, sometimes from pretty much nothing. How does one grow a crop if one has eaten the seeds to avoid starvation the winter before? And how does one survive as a miner when the days of available work shrink from five, to four, to two, to “Mine’s Closed”?

River of Earth, originally published in 1940, is a classic tale of Appalachian coal miners, dirt-poor, ever-proud people living deep in the mountains, crags and hollers, trying to scratch out a living, sometimes from pretty much nothing. How does one grow a crop if one has eaten the seeds to avoid starvation the winter before? And how does one survive as a miner when the days of available work shrink from five, to four, to two, to “Mine’s Closed”?

Initially, I was drawn to this book for two reasons. One is an interest in the early United Mine Workers, a stark, brutal organizing effort that is actually nowhere in this story. I got the book for Christmas upon my own request, and one might expect I’d be disappointed that no union shows up at all here.

And yet I wasn’t. Note that five star rating. My other reason for wanting to read it, is that one of my favorite authors mentions it in the text of one of his novels, and I wrote it down. And as I read this bittersweet tale of rural Caucasian poverty, I found something unexpected. I’ve been finding it more than one might think lately. I found ghosts and echoes of my own ancestors.

My grandfather was a miner; he died of black lung. But when a relative embarked on a genealogical expedition, I found that three of my four grandparents had roots in that same hardscrabble region, the part of Eastern Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia where a body had to more or less guess, back in the 1700’s, which side of the state line he was on.

By 1940, when this book was published, my folks had cleared out of there, but I still heard little speech mannerisms, which cultural geographers call “cultural artifacts”, that had embedded themselves and dropped into the speech of my elders back in the day.

Alpha, usually referred to in the first-person narrative as “Mother”, has married down. She fell in love with Brack many years ago, and although there was at least one wealthy man that set his cap for her, she chose Brack instead. And she doesn’t complain about the family’s state of poverty, not even when there is so little food that she pretends to eat while the children have their supper so that they won’t realize she is making a single mouthful last an entire meal. No, Brack is the one she wanted, and he is what she’s got. She’d do it again, she says.

But oh, how she wants to settle on a little spot of land! At one point they have rented a farm that is humble, yet provides enough food that they can winter over without fear of starvation. It’s on a hilltop with a view, and it has access to woods nearby where in spring, wild salad greens can be picked. It’s all she wants. That, and for Baby Green to survive. He’s been feeling poorly, crying from hunger. Finally, one ugly winter when the food has nearly run out, she apologetically takes a little more food at table. She is ashamed to do it, but she knows the baby needs milk, and it’s the only way she’ll be able to feed him.

She loves that baby so.

Just a plot of land where she can grow things and settle into the house without constantly being required to pick up and move to the next coal town, a mining town which might or might not be hiring, and where the air will clog the children’s lungs and coat the inside of the house with fine black grit, no matter how many used tobacco plugs are stuffed into its cracks. She is sure that if her little family takes care of the earth, it will take care of them. It worked for her mother, and it will work for her family too…if only she can persuade Brack.

And she can’t. Brack is a miner. He believes he was destined to mine coal. And wouldn’t it be nice if his many hanger-on relations, those that come to visit and never leave, felt inclined to do the same? Or to help turn the ground, when they have some to turn? Or to do something other than eat more than anybody else and complain that the food isn’t good enough?

The reader has to admit that this is a wicked-hard dilemma. If one’s relatives are likely to starve if turned out of the house midwinter with nowhere to go, can one send them? But if one’s children are going hungry because the relatives are eating a lot of the food that was supposed to be theirs, can one continue to feed them? It’s a point of contention between Mother and Father. Father says he won’t turn his kin out; Mother says the children are too thin and hungry, and couldn’t his kin do a lick of work for once?

At one point Grandma needs help, but Mother can’t go to her, because the baby is ill. The food supply problem and the Grandma problem are partially solved by sending our narrator and protagonist, still elementary school aged, off to live with her and help her run her farm. Grandma is the embodiment of a work ethic. Rheumatic and 78 years old, she crawls down the rows of crops in order to harvest a few puny potatoes. She reflects on her married life, before her husband died, and her pride in having none of them shot to death, so common in these nail-tough hills:

“Eight me and Boone brought into this world, and every one a wanted child. Four died young, and natural. Three boys and one girl we raised. My boys were a mite stubheaded, as growing ones air. But nary a son I had pleasured himself with shooting off guns, a-rim-recking at Hardin Town and in the camps, a-playing at cards and mixing in knife scrapes, traipsing thar and yon, weaving drunk. Nor they never drew blood for doing’s sake, as I’ve got knowing of. Feisty though, and ready to fight fair fist if the other feller wanted it that a way. I allus said, times come when a feller’s got to fight. Come that time let him strike hard where it’ll do most good, a-measuring stick with stone, best battler win. The devil can’t be fit lessen you use fire.”

It occurred to me as I read it, although I could hear Grandma speak in that dialect in my head clear as day, that the dialect would wreck havoc upon the eyes and mind of someone with a mother tongue other than English. I handed it to my husband and pointed to a paragraph. He’s been in the USA for decades and speaks several languages, but he reluctantly told me that although he could understand it if I read it aloud with inflections where they belonged, it was really too much on the printed page.

With that sole caveat, I recommend this slim but magnificent story. The setting is nearly a character unto itself (although I had to get online to figure out what a paw-paw fruit was). The dialogue and its point and counterpoint, Mother advocating for the Earth, and Father advocating for dynamite and despoilment, is bound to resonate in this fragile ecological time.

But you could just read it because it is amazing literary fiction.

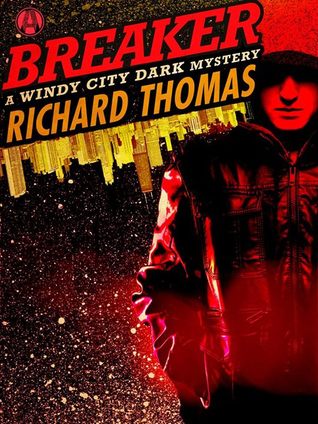

Richard Thomas is a monstrously great writer. In Breaker, a Windy City Dark mystery, he presents us with Ray, a man of unusual and intimidating appearance; a sinister stranger in a white van who victimizes Chicago’s working class school girls; and Natalie, the girl that lives next door to Ray. Though this is the first Windy City Dark mystery I read, I fell in, only extricating myself close to bedtime, because this is not the kind of thing you want entering your dreams. This smashing thriller came to me free of charge from Net Galley and Random House Alibi.

Richard Thomas is a monstrously great writer. In Breaker, a Windy City Dark mystery, he presents us with Ray, a man of unusual and intimidating appearance; a sinister stranger in a white van who victimizes Chicago’s working class school girls; and Natalie, the girl that lives next door to Ray. Though this is the first Windy City Dark mystery I read, I fell in, only extricating myself close to bedtime, because this is not the kind of thing you want entering your dreams. This smashing thriller came to me free of charge from Net Galley and Random House Alibi.