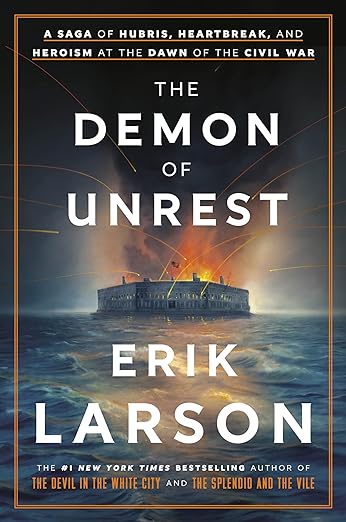

When it comes to history, it’s hard to conjure a more capable author than Erik Larson. I’ve thought this for some time, but his Churchill biography, The Splendid and the Vile (2020) cemented this impression. I am therefore gushingly grateful to NetGalley and Crown Books for the review copy. I would have paid full cover price for this book if that was the only way that I could get it—or the only way that I could get it soon.

This book focuses on Fort Sumter, the Federal fort off the coast of South Carolina that became the catalyst for the opening guns of the American Civil War. The Southern states that seceded from the US, or that attempted to do so, believed themselves entitled to seize the forts, munitions, and indeed, every single ounce of American property located within the borders of their states—and although Fort Sumter and the lesser, partially constructed forts around it were on islands rather than inside the state’s boundaries, they expected to annex those, too.

Meanwhile, as most know, Major Robert Anderson was the fort’s commander, and he desperately wanted orders from Washington. The period following Lincoln’s election, up until he actually took office, was a critical one, but President Buchanan was determined to postpone any official acts until he could hand the responsibility to someone else. He didn’t want his legacy marred by the beginning of a civil war, or indeed, by any sort of noteworthy strife whatsoever, and so he mostly just hid from everyone. Representatives from South Carolina—would-be ambassadors that came to conduct international business—were turned away without official recognition, and that’s about the only worthwhile thing the guy did. And during this fraught period, Anderson and those he commanded waited tensely to learn whether they would be ordered to evacuate, or to defend the fort.

They waited a long damn time; too long.

This is a complex story and an interesting one, and so there are many historical characters discussed, but the primary three that take center stage are Major Anderson; Edmund Ruffin, a South Carolinian firebreather, stoking the fires of secession; and Mary Chesnut, the highly literate wife of a member of the ruling elite. Others of importance are, of course, President Lincoln; Allan Pinkerton, the head of the notorious Pinkerton Agency, which is tasked with keeping Lincoln alive; and a Southern power broker named Hammond, with whom the story begins.

In starting the narrative by discussing Hammond, Ruffin, and Chesnut, Larson gives us a fascinating window into the minds of the South Carolinian ruling elite, known among themselves as “the chivalry.” They style themselves as if they were characters from out of Arthurian legends, placing their own somewhat bizarre code of honor above every other possible principle, and beyond matters of simple practicality. I’ve always been fascinated by the way that leaders of morally bankrupt causes arrange their thoughts and rationales so that they can look at themselves in the mirror every morning and like what they see, and nobody can explain it quite the way Larson can. Everything is crystal clear and meticulously documented. I’m a stickler for documentation, and so although I feel a little silly doing so for someone of his stature, I pull two of his sources, Battle Cry of Freedom, by James McPherson, and Mary Chesnut’s Civil War, which is the diary she wrote leading up to and during the war, from my own shelves, and turn to the pages indicated in a couple of the notes. There they are, just where Larson said they’d be! This may not impress you, but it makes me ridiculously happy.

The story commences with Hammond, a wealthy planter with a highly elastic moral code. There’s a fair amount of trigger worthy material here—though the term had not been coined yet, he was a sexual predator of the highest order, and delighted in writing about the things he did to his nieces. Although this information, drawn from primary sources, does its job by letting us know exactly what kind of person helped shape the rebellion, it’s hard to stomach, and I advise readers that can’t stand it to either skim or skip these passages, because one can easily understand the majority of the text without them.

Once upon a time, this reviewer taught about the American Civil War to teens, and yet I learn a hefty amount of new information. In particular, I find the depiction of Anderson illuminating. I have never seen such a well rendered portrait of him before.

I could discuss this book all day, and very nearly have done so, but the reader will do far better to get the book itself. Highly recommended, this may well be the best nonfiction book of 2024.