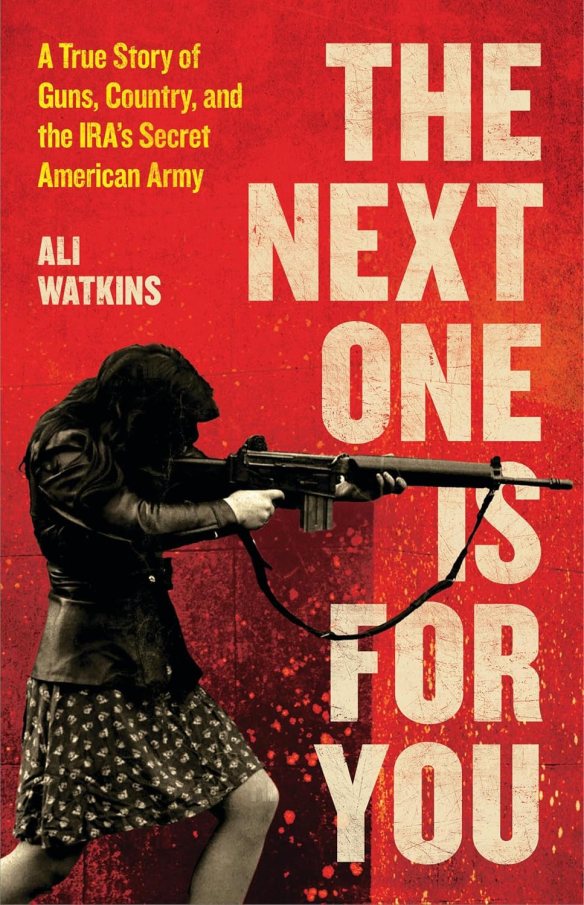

One of the most hotly contested political issues for English speaking people during the 1970s and 1980s was the battle taking place in the North of Ireland between its original inhabitants and the British government. This reviewer was deeply interested in the conflict while it took place, and so when I saw this book, The Next One is for You: A True Story of Guns, Country, and the IRA’s Secret Army, by Ali Watkins,my heart began to pound before I’d read a single page. My thanks go to NetGalley and Little, Brown and Company for the review copy. This book is for sale now.

The fight between the working-class citizens of Belfast and the middle-class Protestants, who worked hand in glove with the British Crown, has roots that are centuries deep. Watkins reviews these without going into the weeds, and leads us up to modern times succinctly. I appreciate her fair discussion of the manner in which the Irish Republican Army, or IRA, developed and burgeoned. (U.S. readers new to the topic should know that ‘Republican’ was part of the name due to a desire for the Irish Northern counties to be restored to the Republic of Ireland, not because of any political similarities to the Republican party in the U.S.A.) Initially the movement was modeled on the Civil Rights Movement of the United States, with large, peaceful marches; there were signs, songs and speeches given. People packed lunches and took their children with them. But these protests were violently repulsed, with police and the military surrounding the participants so that there was no escape, and then shooting them like wooden ducks in an arcade.

Poverty was widespread in Belfast and its surrounding areas, with few jobs, and miserable living conditions in government subsidized apartments. “A Catholic surname got you passed over for jobs, if you even got the chance to apply.” There was no Bill of Rights, and when armed forces chose to search someone’s home, they announced themselves by kicking the door in. The situation was intolerable. And so, when peaceful protest was no longer possible, there were two choices remaining: armed struggle or defeat. “The goal: to expel the British from Northern Ireland, whatever the cost.”

Because such a large portion of the U.S. population is of Irish descent, these circumstances were of great interest in America. When the IRA broke off from the more traditional, less militant (and ineffective) organization that already existed, it wasn’t long before many Americans wanted to help in some way. Two organizations developed in the States, and this is much of what Watkins discusses. Clan na Gael was an Irish solidarity organization that had existed in the U.S. since 1867. It became an important element in the Irish struggle, organizing politically, and raising funds. But in order to gain widespread appeal, there needed to be an additional organization that existed for those that wanted to contribute financially to the poor of Belfast without also supporting the armed fight. In 1969, NORAID was born.

A disclosure: this reviewer was a great supporter of both organizations during that time. In fact, I once won a raffle from the Clan, which netted me a wheelbarrow of whiskey! Since I don’t drink, I took one bottle for my spouse and donated the rest back to the Clan. I never joined the Clan, primarily because I wasn’t asked.

Watkins discusses the history of both organizations as well as the key individuals that brought them about. She does a magnificent job and brings a treasure trove of outstanding documentation, right up until nearly the end of the book, at which point she inexplicably lapses into the journo-speak of the period, blathering about “senseless violence” in an abrupt shift that made my jaw drop. She had already explained, very capably, just why a nonviolent struggle was completely impossible. The devastating numbers of Irish youth that died during this campaign is indeed heartbreaking, but at the same time, just what else were they supposed to do? No foreign government was even remotely interested in assisting them; the British government was a key ally of the U.S. government, and had something of a headlock on its protectorates. And while I respect that the author had to conclude the book in one way or another, just admitting that there was no clear solution would have been vastly better than parroting American mainstream media of the time period. What the what?

Nevertheless, those with an interest in this struggle should get this book and read it. Just bear the ending with a grain of salt.

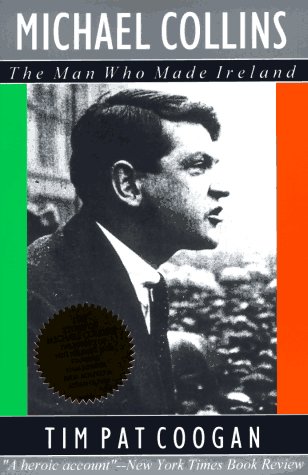

To date, this is the single best volume that’s been written about Collins, and it’s a meal. I purchased this title on an annual pilgrimage to Powell’s City of Books in Portland, Oregon when I was there to visit family a few years ago. Although the length of the book is listed as 480 pages in paperback, the reader needs to come prepared. The type is tiny and dense, and it took me a long time to wade through it. If it were formatted using more standard guidelines, it would be a great deal longer.

To date, this is the single best volume that’s been written about Collins, and it’s a meal. I purchased this title on an annual pilgrimage to Powell’s City of Books in Portland, Oregon when I was there to visit family a few years ago. Although the length of the book is listed as 480 pages in paperback, the reader needs to come prepared. The type is tiny and dense, and it took me a long time to wade through it. If it were formatted using more standard guidelines, it would be a great deal longer.