Chameleo is a twisted but true story of an addict who unwittingly becomes an experimental subject in a classified government research program, and the bizarre events that took place then and in the aftermath. My thanks go to the author, who provided me with a copy in exchange for an honest review.

Chameleo is a twisted but true story of an addict who unwittingly becomes an experimental subject in a classified government research program, and the bizarre events that took place then and in the aftermath. My thanks go to the author, who provided me with a copy in exchange for an honest review.

Dion Fuller (not the person’s actual name) had been released from a psychiatric hospital in Southern California. He had procured some heroine and nodded off, permitting various equally marginal characters access to his home. Sometimes he was out of it and had no idea what was happening. It was likely during this time that the guy with the stolen classified documents and a couple dozen pairs of night-vision goggles belonging to the US government made his way into Dion’s apartment. The ensuing chaos proves once and for all that just because a person is crazy does not mean nobody is out to get them. Just ask Dion!

Guffey, the author, is a Cal State creative writing teacher who found himself involved in Dion’s situation. He had a free term at the same time that Dion, an old childhood friend, called for help. With a certain amount of necessary remove, he did his best to advise his friend while taking copious notes. Soon he became convinced that his old friend was not hallucinating.

“Imagine a ridiculous college fraternity with the resources of the entire black budget of the United States of America deciding to play one long prank on some faceless guy in San Diego. And imagine that the faceless guy is you.”

The author’s description of a malicious antic known as “Street Theater” in government circles reminded me of the dirty tricks that the Democratic Party played on the Nixon camp during the early 1960’s—cruising into town in advance, for example, and moving street signs around so that the Republicans would get lost and be late to a speaking engagement—which were later used in turn by Nixon’s Committee to Re-Elect the President in 1972. Dion hoped that leaving his home, which was located very near a Naval installation, would make it all stop, and it did. He left California and headed cross country, but every time he got close to a US military installation, a whole train of personnel would follow him once more, like a trail of ducklings after their mother, right out there in the middle of the freaking desert.

Guffey’s story, which includes the Masons, the Illuminati (note the cover), and assorted other conspiratorial ingredients that would ordinarily cause me to stay completely fucking clear of this whacked out tale, follows Dion as far north as Minnesota, then oh dear God, to Seattle where Guffey was staying. But just as it seems it can’t get any more strange and stressful, the whole thing becomes hilarious! Your humble reviewer sat and laughed out loud about two-thirds of the way into the story, and the lighter tone that marks the book until near the end is what prevents the whole thing from degenerating into a bottomless abyss.

My only quibble with this story—and it’s a small one—is that if we must read entire transcribed passages of conversations, then the persons involved in the conversation in question should all be named, with no pseudonyms involved, so that the reader can use that transcript as a primary document if they want or need to. If that can’t happen, then some of these conversations ought to be summarized or paraphrased, at least in places. But this shouldn’t keep you from getting a copy of this memoir and reading it.

In fact, those that question authority and wonder just how far the US government has strayed from its stated ideals will welcome this strange little book, which is just well documented enough to convince me that it’s entirely true.

It’s available for purchase now.

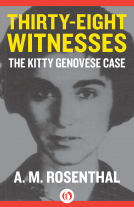

AM Rosenthal was a journalist, but in the 1960’s he was moved to write this relatively brief book—if fictional it would be considered a novella—about the failure of neighboring New Yorkers to come to the aid of Kitty Genovese, a woman that was murdered in 1964. I received this DRC free of charge from Net Galley and Open Road Integrated Media in exchange for an honest review.

AM Rosenthal was a journalist, but in the 1960’s he was moved to write this relatively brief book—if fictional it would be considered a novella—about the failure of neighboring New Yorkers to come to the aid of Kitty Genovese, a woman that was murdered in 1964. I received this DRC free of charge from Net Galley and Open Road Integrated Media in exchange for an honest review.