3.5 stars, rounded upward.

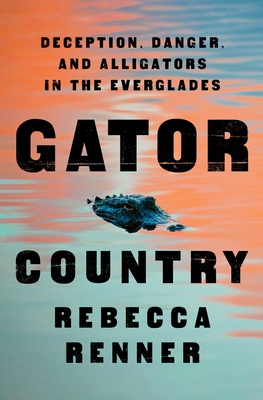

Rebecca Renner is a journalist who has written for National Geographic and a host of other prestigious newspapers and magazines. Gator Country is her first book. Lucky me, I read it free and early. My thanks go to Macmillan Audio and Net Galley for the review copy. This book is for sale now.

Gator Country is the true story of wildlife officer Jeff Babouta and the sting that brought in a number of poachers and slowed the ravaging of the alligator population in the Florida Everglades. Babouta is coasting toward retirement when he is approached, and although he is reluctant, he is eventually convinced that he is the best qualified officer to carry out this assignment. To do it, he has to live away from his family for years, posing as a newbie gator farmer. This is a legal profession, but it’s also one that is rife with poachers. In order to bring the poachers in, he must first convince them to mentor him and befriend him in his farming operation. He spends years gaining their trust and learning from them, but then has to turn them in.

I thought hard about whether to read this book, because generally speaking, I don’t have warm feelings toward cops, and the past ten years have intensified that sentiment. But rangers and other wildlife cops are a bit more ambiguous; some of them do more good than harm. So it is with Babouta.

There are, Renner tells us, basically two types of poachers. Some are the small, independent people that she says are just trying to feed their families, and some are the large scale despoilers, those working on a large scale to provide gator parts to buyers from China, where they are prized for their medicinal properties and folk cures. Renner is sympathetic toward the former but not the latter.

In following Babouta’s story I pick up odd bits of knowledge. I have never been to the Everglades, nor do I plan to, and so had I not read this book, I would probably never have known that there are bottlenose dolphins there. Who knew? There are a number of such tidbits that I pick up along the way, and this is one of the best things about reading—or listening to—nonfiction.

That said, the audio becomes a complicated read for two reasons. One is that the narrative skips around a great deal. The main part is Babouta’s, but we also hear about Peg Brown, a legendary poacher whose name keeps coming up as Babouta converses with his new colleagues. I have no idea why I or any reader needs to know so much about the guy; from where I sit, Brown hasn’t earned his place in this book, but then it’s not my book. The story is needlessly complicated by Brown as well as a handful of other bits that are woven into the narrative, such as the journalist following along, and we would be better off without these.

The other issue with the audio is that when we shift the point of view, the person whose story we’re hearing has exactly the same voice as Babouta. Now and then I would have to pause and run it back, just to figure out who we’re talking about, or hearing from.

Even though the synopsis makes it crystal clear that the book is about wildlife poaching, rather than an alligator version of Jaws, I expected to hear of some close calls, some scary moments. But the scary moments are mostly about humans.

At the beginning, this book was such a snooze that in order to force myself to keep listening, I found other things to do with my hands. About a third of the way in, however, the story woke up, and after that I was mostly interested, apart from the occasional divergence of topic and point of view. For those that are sufficiently interested to want to read this book, I recommend that you either stick to the print version, or if you strongly favor the audio, get the print version to help you stay oriented and follow along. I would also try to get it free or cheap, unless you have an endless amount of cash to burn.