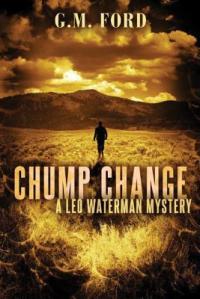

There are a number of masters of the mystery genre that I read faithfully. There are about a dozen, if we count those no longer among us (such as Ed McBain, Donald Westlake, and Tony Hillerman) whose novels I would read simply on the basis of their authorship.

GM Ford is among my dozen. In fact, he’s toward the top of the heap. I can’t objectively say whether the latter is because he sets his mysteries here in my own stomping grounds–so that while James Lee Burke can give me a really great travelogue, when Ford hooks a left on Madison and heads to Madison Park, I am looking out the front of the car windshield with him, since we’re less than twenty minutes from my home.

But the one thing I can say with objective certainty is that he is one fine writer. He can take a premise that is as old as the hills and in the hands of a lesser writer would cause me to moan, “Oh, come ON, not THIS again!” and give it a twist to turn it into something else, so NOT really ‘this again’, and then write it with such amazing deftness, word-smithery, pacing, and wry humor that I almost can’t put it down.

But I do. I put it down at bedtime, because I’m going to read SOMETHING after I take my sleeping aid for the night, and whatever it is, I may not remember it very well. My very favorite reading material only gets read while my brain is in fully active mode. I doled this out to myself in bits and pieces, like Mary Ingalls hoarding her Christmas candy. Ohhh, don’t let it be over yet!

But I don’t delay gratification all that well, and as the weekend hazes to a close, the last page of the book terminated, and now I must wait for the one that will be out in a few months.

I had half a dozen sticky-noted quotes to toss your way, poignant moments with “the boys”, as the first-person protagonist fondly refers to his late father’s crowd, some of whom are truly as down-and-out as people can be, living beneath freeways, in doorways, and under trees in city parks. His trenchant observation that “the line between middle class and out on your ass is thinner than a piece of Denny’s bacon” is most painfully clear in pricey metropolises such as Seattle, where the annual take-home pay of a waitress or clerical worker would not even pay the rent for an studio apartment in the city, let alone allow for other costs of daily living like food, transportation, medical premiums, and clothing.

And for me, this recognition is one of the key grooves that turns my mental tumblers into place and permits me to feel empathy toward an author. It’s a hard world out there, and even in a glorious place like Seattle, poverty’s knife edge is closer to most of us than we care to even acknowledge.

Leo Waterman, our intrepid detective, has inherited enough to live off of, having come of age at a middling forty-five, but life has already taught him what down-and-out looks like. He feels the bumps on the head and the shock that strikes his skeleton when he climbs a fence and jumps to the concrete on the other side, but if there’s a good enough reason, he does it anyway. He doesn’t have a death wish, but he has the character and integrity to go out and butt heads with bad people when the city’s cops settle in more comfortably behind their desks and wait for retirement to edge ever closer. Leo’s an easy hero to bond with.

As for the rest of the little bookmarks and sticky notes I have reluctantly pulled from my still-new book’s pages…why ruin it for you? It doesn’t get much better than this. Find the quotes for yourself. You can order that book and it will be at your gates inside the week. But you can’t have my copy. It’s been claimed by another family member, even as I typed this review.

Jance’s JP Beaumont detective series is one of my all-time favorites. Set (usually) in my own home town, it carries a gritty yet human, thoroughly believable flavor that I just can’t find anywhere else.

Jance’s JP Beaumont detective series is one of my all-time favorites. Set (usually) in my own home town, it carries a gritty yet human, thoroughly believable flavor that I just can’t find anywhere else.