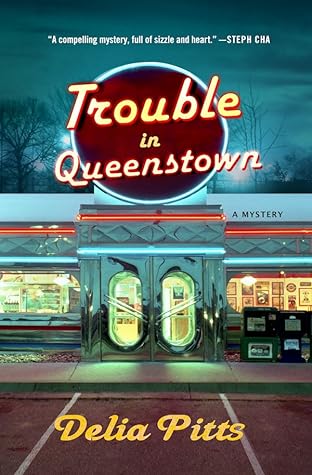

Delia Pitts has been writing mysteries for quite some time, but she is new to me. In Trouble in Queenstown, she introduces hardboiled sleuth Evander Myrick. Myrick’s friends call her Vandy, and that helps to distinguish her from her elderly father for whom she is named; he’s in a memory care unit.

My thanks go to NetGalley, Macmillan Audio, and St. Martin’s Press for the review copies. This book is for sale now.

At first glance, I thought that this detective fiction was set in New Zealand. Queenstown, right? But in this case, the locale is Queenstown, New Jersey. The story opens with Vandy cleaning up a mess in her office just as Leo Hannah storms in and wants to see Evander Myrick. He assumes Myrick will be a Caucasian male, and that Myrick herself is a member of the cleaning staff.

Oops.

Hannah comes to hire Vandy in the wake of his wife’s murder. He knows exactly who did it, he tells her, and he wants her to prove it, starting with some surveillance. Vandy isn’t sure she should take this job, but she has to pay top dollar to keep her daddy in the best facility, so she reluctantly signs on. As the story progresses, there are numerous twists and turns, and the violence escalates. By the story’s end, three different people have tried to hire her for exactly the same case!

The thing I appreciate here is the way Pitts addresses cop racism. So many detective novels require the reader to suspend belief, to assume that every cop is fearlessly dedicated to finding out the unvarnished truth and arresting the perpetrator of the crime, regardless of race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. But as Vandy conducts her investigation, Pitts keeps it real. At one point the detective speaks with a salon stylist that worked on Ivy’s hair, and he tells her that Ivy was afraid of someone at home. Vandy asks if he contacted the police.

“’The police?’ He jerked his neck, pursing his lips as if I’d farted. ‘Girl, you think the cops came here?’ He sniffed. ‘You don’t look like a fool. Maybe I read you wrong.’”

Sadly, the second half of the book doesn’t impress me as much as the first half does. I have a short list of tropes that I never want to see again in a mystery novel, and she trips a few, including my most hated one. I won’t go into details because it’s too far into the story, and I don’t want to spoil anything, but when it appears, I sit back, disengage from the text, and roll my eyes. Ohhh buh-ruther. As I continue reading, I can see who the murderer is well in advance, and the climax itself is a bit over the top, though without the tropes, I mightn’t have noticed this last issue.

In addition to the digital review copy, I have the audio. The reader does a fine job.

The more mysteries a person reads, the staler tropes become. I am perhaps more sensitive than most readers, having logged over a thousand novels in this genre. Readers that have not read many mysteries are less likely to be aware of, and therefore bothered by overused elements, and so this book may please you much more than it did me. But for hardened, crochety old readers such as myself, I recommend getting this book free or cheap, if you choose to read it. Newer readers may enjoy it enough to justify the sticker price.

Well now, that was a meal. Penzler does nothing halfway, and this meaty collection of 74 stories took me awhile to move through. I read most, but not all, and I’ll get to that in a minute. First, though, thanks go to Net Galley and Doubleday for the review copy. This book is for sale now.

Well now, that was a meal. Penzler does nothing halfway, and this meaty collection of 74 stories took me awhile to move through. I read most, but not all, and I’ll get to that in a minute. First, though, thanks go to Net Galley and Doubleday for the review copy. This book is for sale now.